Muslim Women

WOMEN, throughout the history of Islam, have played significant roles and, by their feats, have demonstrated not only the vast arena which Islam affords them for the performance of noble and heroic deeds, but also the exaltedness of the position accorded to women in Islamic society.

Within the sphere of lslam, ‘Aishah, the daughter of Abu Bakr and wife of the Prophet, stands out as a woman of notable intelligence, whose intellectual gifts were fittingly utilized in the service of Islam. Very young in comparison with the Prophet, she survived him by almost half a century, during which period she became a great and authentic source of religious learning for the ummah (community). This was largely due to the accuracy with which she had preserved in her memory the speeches, conversations and sayings of the Prophet. In all, she related about 2210 of his sayings and was extraordinarily gifted in being able to formulate laws from them. It is said that no less than one quarter of the shari’ah injunctions have been derived from her narrations. Her knowledge and deep perception in religious matters was so established that whenever the Companions of the Prophet found themselves in disagreement over any religious matter, they would come to her to seek her assistance. According to Abu Musa ‘Ashari, whenever they were in any doubt as to the meaning of any part of the hadith, they would turn to ‘Aishah. It was seldom that she was unable to solve their problems.62

Although the Encyclopaedia Britannica mentions her as ‘Aishah, the third wife of the Prophet Muhammad, who played a role of some political importance after the Prophet’s death,’63 her real importance is not that of her own individual superiority in Islamic history, but the indication her position gives of the high status women were accorded within the sphere of Islam, and of the vastness of the field in which their talents might honorably be used. It was owing to the distinctive character of Islam that she was able to render such important social and political services.

We present below some additional examples of women who played an effective role in Islam.

TWO REMARKABLE WOMEN

When the Judaic era was drawing to a close, a woman had to be singled out who would in every way be fit to become the mother of one so miraculous in nature as the Prophet Jesus, upon whom be peace. God had ordained that the final prophet of the Jewish people was to be born without a father: the character of his mother had, therefore, to be one of irreproachable innocence and chastity. Mary, who subsequently became known as the Virgin Mary, was found to have lived her life according to this exacting standard, and, by her extraordinary chastity, had proved herself fit to be chosen as the mother of Jesus.

In one of the most authentic collections of the hadith by Bukhari, the Prophet is recorded as saying, “The best woman out of all of them (the Jewish people) was Mary (mother of Jesus), the daughter of ‘Imran, and the best woman out of all of my own people was Khadijah bint Khuwaylid.”64 (This saying was passed on by ‘Ali, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law.) The special historical status that both Khadijah and Mary enjoyed was due to their both having given themselves up entirely to God: they both subordinated their own wills to that of the Almighty.

In the case of Khadijah, she was chosen by God to be the life partner of the final Prophet, Muhammad, because the circumstances of his life were such that he needed someone of superlative virtue, who would put herself and her property entirely in his hands without ever raising her voice in complaint. She did, indeed, give up everything—her life, her property, her leisure and her comfort—for the sake of the Holy Prophet. Although her life, as a result, was one of severe affliction, she was never heard to protest. It was these qualities then that made her worthy in the eyes of God to become the life companion of His Final Prophet. What was the underlying cause of her superiority? Here are two parts of the hadith which throw some light on this.

‘Aishah says that the only other wife of the Prophet that she ever felt envious of was Khadijah, even though she was not a contemporary of hers. “Whenever the Prophet sacrificed a goat,” says ‘Aishah, “he would tell me to send some meat to Khadijah’s friends.” One day I became annoyed, “Oh no, not Khadijah again!” I exclaimed, whereupon the Prophet replied, “I have been intoxicated with her love.”65

According to ‘Aishah, the Prophet would not leave home without praising Khadijah. “One day when he mentioned Khadijah, I became annoyed and said, ‘She was just an old woman. In her stead, God has given you one who is better.’ This angered the Prophet, who said, ‘God knows, He has given me no better than her. She believed when others disbelieved. She had faith in me when others rejected me. She supported me with her wealth when others left me in the lurch. And God gave me children by her, which He has not given me by any other wives.’”66

In every age, there is a need not only for men but also for women to devote themselves to the mission of Islam. Ideally, they should be individuals who are willing in the way that Khadijah was, to involve themselves unstintingly in the scheme of God. Such people are like small cogs which revolve strictly according to the motion of a larger wheel—in this case, the will of God. This is undoubtedly a trying task; but it is also one that carries a great reward. To perform this task is “to help God.” There can be no doubt about the excellence and superiority of those whom God chooses to enlist as His helpers.

THE IDEAL LIFE COMPANION

One of Khadijah’s most significant contributions to the furtherance of Islam was the reassurance which she gave to the Prophet on the occasion of his receiving the first divine revelation in the solitude of the Cave of Hira from the Archangel Gabriel. This was an experience which left the Prophet awestruck and trembling with fear. When he returned to his home, he was still overwhelmed by a feeling of dread and, as he entered, he asked Khadijah to wrap him in a blanket. After some time, when in some measure he had regained his mental equilibrium, he related the entire experience to her, expressing his fears that his life was in danger. She hastened to reassure him, and comforted him by observing, “It cannot be. God will surely never forsake you. You are kind to your kin; you always help the weak; you solace the weary; you take care of whoever crosses your threshold; you speak the truth.”67

Then it occurred to Khadijah that she had best make enquiries of some learned Christians who, well, versed as they were in the scriptures, were bound to have knowledge of revelation and prophethood. She went first to a rahib (hermit) who lived near Mecca. On seeing her, the priest asked, “O noble lady of the Quraysh, what has brought you here?” Khadijah replied, “I have come here to ask you about Gabriel” To this the rahib said, “Glory be to God, he is God’s pure angel. He visits prophets: he came to Jesus and Moses.” Then Khadijah went to another Christian called Addas. She put the same question to him, and he too told her that Gabriel was an angel of God, the very same who had been with Moses when God drowned the Pharaoh. He had also come to Jesus, and through him God had helped Jesus.68

Then Khadijah hastened to Waraqah ibn Nawfal, a Christian convert who had translated part of the Bible into Arabic. When she had finished telling him of what Muhammad had seen and heard, Waraqah exclaimed, “Holy, holy! By the Master of my soul, if your report be true, O Khadijah, this must be the great spirit who spoke to Moses. This means that Muhammad must be the Prophet of this nation.”69 On a subsequent visit, Khadijah brought Muhammad to meet Waraqah ibn Nawfal. Muhammad related the events exactly as they had taken place and, when he had finished, Waraqah said, “By the Master of my soul, I swear that you are the same Prophet whose coming was foretold by Jesus, son of Mary.” But then Waraqah sounded a note of warning: “You will be denied and you will be hurt. You will be abused and you will be pursued.” He nevertheless immediately pledged himself to the Prophet: “If I should ever live to see that day, I should surely help you.”70

ABSOLUTE FREEDOM

Zihar was an old pagan custom among the Arabs which permitted a husband to nullify his wife’s right to consider herself his lawful spouse. All he had to do was utter the words, “anti1alayiya ka zahr ummi,” meaning, “be to me as my mother’s back.” He was then free of conjugal responsibilities, but the wife was not thereby set free to leave her husband’s home or to contract a second marriage.

It happened once in Medina that a Muslim by the name of Aws ibn as-Samit cast off his wife, Khawlah bint Tha’labah, by uttering the fateful words. This was particularly hard on Khawlah, who loved her husband and had little children to support. She lacked the means to provide for her children, but, according to the convention of zihar, she could not claim any support from her husband. She came, therefore, to the Prophet, laid the whole case before him and urged him to assist her. But, since up to that point no revelation had been made to the Prophet on this subject, he could only reply that she was no longer the lawful wife of her husband.

On hearing this, Khawlah began to lament the ruin of her home and the penury into which she and her children would sink. She also told the Prophet that her husband had not expressly stated that he was divorcing her. But the Prophet could give her no positive answer, because he thought that by Arab custom, the separation must already have taken place. Then Khawlah could only weep and pray to God to save her from ruin.71

It was on this occasion that the surah 58 of the Quran entitled, al-Mujadilah (She Who Pleaded), was revealed. It begins with these words:

God has indeed heard the statement of the woman who pleads with thee concerning her husband, and carries her complaint to God. And God always hears the argument between both sides among you, for God hears and sees all things.72

On the basis of this revelation, the justice of her plea was recognized, and this iniquitous custom, based as it was on a false set of values, was finally abolished.

Much later, when Khawlah was an old woman, she once met ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, who had by that time become the Caliph of the Islamic Empire. ‘Umar greeted her and she returned his greeting. Then she said: “O ‘Umar, there was a time when I saw you in the marketplace of ‘Ukaz. Then you were called ‘Umayr73 and you would set your goats to grazing with a stick in your hand. Then, the times changed and you came to be called ‘Umar. Later you became the Chief of the Faithful. Be God-fearing in dealing with your subjects and remember, that for one who fears God’s chastisement, a distantly related man is like a close relative; and one who does not fear death risks the loss of all that he seeks to gain.”

One Jarud Abdi, who was in the company of ‘Umar at that time, exclaimed, “O woman, you have been impudent to the Commander of the Faithful!” But ‘Umar immediately silenced him by saying, “Let her speak. You know who she is. She is the one whose plea was heard above the seventh heaven. She, above all others, deserves to be heard out by ‘Umar.”74

DIVISION OF LABOR

Islam has assigned separate spheres to men and women, the former having the management of all non-domestic, external matters, and the latter being completely in charge of the home. The ensuing division of labor is justifiable in terms not only of biological and physiological differences, but also of the social benefits which stem there from. One important benefit resulting from men and women functioning in different spheres is that they can see each others’ lives objectively, without that sense of personal involvement which tends to cloud their judgement and lead to a damaging emotionalism. They are better able to counsel each other wisely, to give moral support at critical moments, and to offer the daily encouragement with which every successful union should be marked. Experience has repeatedly shown that when one is confronted by a serious problem, one is often initially incapable of arriving at a well• reasoned, objective judgement of the situation. It is only when there is some sympathetic adviser present, who is personally uninvolved in one’s predicament, that solutions begin to present themselves. With men and women having their activities in separate spheres, they are in a better position to bring objective opinions to bear in such difficult situations and can give truly helpful advice in an unemotional and coolly detached way.

In Islamic history, there are many examples of women who have helped their husbands when faced with critical situations. One of the most notable was Khadijah, who successfully brought the Prophet back to a state of normalcy after his experience in the Cave of Hira.

Similarly, when the Prophet entered into the Treaty of al-Hudaybiyyah, he felt severely afflicted by his own people’s display of dissatisfaction with the terms of the Treaty, which, in their opinion, made far too many concessions to their enemies, the Quraysh. The Companions felt, in fact, that in accepting humiliating peace terms, they were bowing to the enemy. However, even in the face of such sentiments, the Prophet ordered his people to sacrifice the animals they had brought with them, and to shave their heads.75 No one got up to obey his order. The Prophet repeated his order three times, but no one stirred from his place. This was extremely disconcerting, for never had an order given by the Prophet been deliberately ignored. The Prophet, dismayed at the resentment shown by the Muslims, returned to his tent and to the company of his wife, Umm Salmah. Seeing him look so grieved, she asked him what ailed him. The Prophet then told her of this unprecedented refusal to obey his order. Umm Salmah then said, “O Messenger of God, if you are convinced that your judgement is right, you should go outside, and, without a word to anyone, slaughter your animal and shave your head.”76

The Prophet did exactly as she had suggested. He went out, sacrificed his animal and shaved his head. When the people saw what he had done, they immediately began to follow suit.

Their anguish was so great that it seemed they would cut one another’s heads as they began to shave them after the sacrifice.

The reason that Khadijah and Umm Salmah were able to arrive at a correct judgment in such delicate situations was that they were detached from them and, therefore, in a position to offer objective opinions. If they too had been seriously involved, they might have been too subjective in their thinking.

WOMAN—AS A SOURCE OF KNOWLEDGE

There is a famous saying of the Prophet that the acquisition of knowledge is the duty of all Muslims.77 In this saying, the word muslim is in the masculine form, muslimah being the feminine form, but the work of scholars carried out on the traditions makes it clear that muslimah may be legitimately inferred. That means that the acquisition of knowledge is likewise the duty of Muslim women.

In the biographies of the narrators of Hadith literature, mention is made of the academic services of women, which is a clear indication that during the first era of Islam, there was a strong tendency among women to acquire knowledge. The benefits ensuing from their efforts were far-reaching. For example Imam Bukhari, whose al-Jami’ as-Sahih is by far the most authentic source of Hadith learning, set off, when he was 14 years of age, to acquire knowledge from far distant scholars: if he was in a position to appreciate the lessons given by the great teachers of the time, it was because his mother and sister had given him a sound educational background at home. It is said that Imam ibn Jauzi, the famous religious scholar, received his primary education from his aunt. Ibn Abi Asiba’s sister and daughter were experts in medicine—the lady doctors of their time. And among the Hadith teachers of Imam ibn Asakir, several women teachers are mentioned.

During the first era of Islam, academic activity related mostly to work on the Hadith and athar.78 We find, in this age, that a number of the Prophet’s Companions were women, and that they contributed in large measure to the narration and preservation of the traditions of the Prophet. The Prophet’s wife, ‘Aishah, herself handed down to posterity a substantial proportion of what comprises the vast whole of Islamic knowledge. The next generation of women in their turn handed down the traditions which they had heard at first hand from the Prophet or his Companions. Many of them acquired their knowledge from religious scholars to whom they were related and carried on the good work of passing it on to their successors.

ISLAM GIVES COURAGE

Tumadir bint ‘Amr ibn ath-Tharid as-Sulamiyya (d.24 A.H), a poetess, later known as Khansa, who was born into a noble family (her father was the Chief of the Banu Salim tribe of Mudar), lost her two brothers in a war fought prior to the advent of Islam. Their deaths were a great shock to her. Before this tragedy it had been her wont to compose just two or three couplets at a time, but now, after her bereavement, the verses simply flowed from her heart as the tears flowed from her eyes. The elegies she wrote in memory of her brothers, particularly Sakhr, were heart-rending: she continued to write and lament until she became blind in both eyes.

After the fall of Mecca, she came to the Prophet with her tribe and accepted Islam. It is related that when she read out some of her verses to the Prophet, he was very moved, and asked her to continue reading.

In her youth, she had been unable to bear the tragedy of her brothers’ deaths, but she derived such strength from Islam that, in her old age, she sacrificed her own sons in the path of God. She had four sons, all of whom she persuaded to fight in the battle of Qadsiya. They all fought bravely and were finally martyred. When she received the news of the deaths of all of her sons, she neither wrote elegies, nor did she bewail their passing. Instead, she heard the news with great calm and fortitude, and said: “Thank God who has awarded me the honor of their martyrdom. I hope God will bring us together in the life Hereafter.”79

PATIENCE FOR PARADISE

It is related that in the early days of Islam, the Prophet was once passing in the vicinity of Yasir and his family in Mecca when they were being subjected to the violence of the Quraysh. When Yasir set eyes on the Prophet, the only question he asked him was, “O Prophet of God, is this all there is to the world?” The Prophet replied, “O family of Yasir, be patient, for you have been promised heaven.”80 Yasir and his wife Summaiyah were the first to succumb to persecution by the Quraysh. Yet, even after seeing the painful fate which his parents had suffered, ‘Ammar, their son, being strong of will, did not flinch from his faith. It is said that ‘Ammar ibn Yasir was the first Meccan Muslim to have built a mosque in his home. It is believed that it is he who is referred to in this verse of the Quran:81

Can he who passes his night in adoration, standing up or on his knees, who dreads the terrors of the life to come and hopes to earn the mercy of his Lord, be compared to the unbeliever? ... Truly, none will take heed but men of understanding.82

IN THE FIELD OF ACTION

The general lot of women in the early days of Islam was frequently a hard one, but they bore themselves with remarkable fortitude and adapted themselves to whatever conditions they found themselves in. One shining example is that of Abu Bakr’s daughter Asma’, who was born 27 years before the Emigration. When she accepted Islam in Mecca, the Muslims were just 17 in number.

When Abu Bakr emigrated to Medina, he possessed 6000 dirhams, all of which he took with him. When his father, Abu Qahafa, heard of this, he came to his family to console them and said, “I think that Abu Bakr has not only given us a shock by leaving you alone, but I suppose he has also taken all the money with him.” Asma’ then told her grandfather that he had left them well provided for. She thereupon collected some small stones and with them she filled up the niche where Abu Bakr had formerly kept his money. She covered the pile of stones with a cloth and then placed her grandfather’s hand on it. Having gone blind in his old age, he was easily taken in by this trick, and thought that the niche was full of dirhams. “It is a good thing that Abu Bakr has done. This will suffice for your necessities.” Asma’ then confessed that her father had not left them a single dirham and that it was only to comfort her grandfather that she had conceived of this idea.83

Before the advent of Islam, Asma’s father had been one of the richest merchants of Mecca, but when Asma’ emigrated to Medina with her husband, Zubayr, they had to live in the harshest of conditions. Bukhari has recorded Asma’s account of how her own existence was eked out from day to day:

When I married Zubayr, he had neither wealth nor property, nor anything else. He had no servant, and there was only one camel to bring water and only one horse. I myself brought the grass for the camel and crushed date stones for it to eat instead of grain. I had to fetch the water myself, and when the water bag burst I would sew it up myself. As well as managing the house, I had also to take care of the horse. This I found the most difficult of all. I did not know how to cook the bread properly, so whenever I had to make it, I would knead the flour and take it to the Ansar women in the neighbourhood. They were very sincere women and they would cook my bread along with their own. When Zubayr reached Medina, the Prophet gave him a piece of land which was two miles away from the city. I used to work on this land, and on the way back home I would carry a sack of date stones on my head.

One day, when I was returning like this with a sack on my head, I saw the Prophet mounted on a camel going along the road with a group of Medinan Muslims. When he saw me, he reined in his camel and signed to me to sit on it, but I felt shy of travelling With men, and I also thought that Zubayr might take offence at this, as he was very sensitive about his honor. The Prophet, realizing that I was hesitant, did not insist, and went on his way.

When I came home, I told Zubayr the whole story. I said that I had felt shy of sitting with the men on the camel and that I had also remembered his sense of honor. To this Zubayr replied, “By God, your carrying date stones home on your head is harder for me to bear than that.”84

Such instances of how women toiled during their stay in Medina are numberless. At that time women worked not only in their homes, but outside as well. This was because their menfolk were so preoccupied with preaching Islam that there was little time left in which to discharge their household responsibilities. It was left to the women then to deal with both internal and external duties. They even tended the animals, did the farming and worked in the orchards.

THE VIRTUE OF BELIEVING WOMEN

When this verse was revealed in the Quran—“They who hoard up gold and silver and spend it not in the way of God, unto them give tidings of a painful doom”85—then the Prophet said: “Woe to gold, woe to silver.” When the Companions of the Prophet learned of this they were upset. They began to ask one another what things they were going to store then. At that time ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab was with them. ‘Umar said, if they liked, he could put this matter to the Prophet. Everyone agreed, so ‘Umar went to the Prophet and said, “The Companions are saying, ‘Could we but learn which kind of wealth is better, we would store that and no other.’ The Prophet said: ‘Everyone should possess a tongue which remembers God, a heart that thanks God and a wife that helps him in his faith.”’86 Another version has used the word “Hereafter” for faith.

WOMEN IN EVERY FIELD

Once Umm Salmah was having her hair combed when she heard the sermon starting in the mosque. The Prophet began with the words, “O people ...” On hearing this she told the woman who was combing her hair to braid it just as it was. The woman asked her why she was in such a hurry. Umm Salmah replied, “Are we not counted among ‘people’?” And so saying, she promptly braided her hair herself, went to the corner of the house nearest the mosque and listened to the sermon.

In all, Umm Salmah related 378 traditions and used to lay down laws. Ibn Qayyim writes that if her decrees were to be compiled, they would take up a whole book.

Out of all the Prophet’s wives, ‘Aishah was the most intelligent. About 2210 traditions of the Prophet were related by her, and these were passed on by about one hundred of the Prophet’s Companions and their close associates. Among her pupils were such eminent scholars as ‘Urwah ibn Zubayr, Sa’id ibn Mussayyib, ‘Abdullah ibn ‘Amir, Mashruq, ‘Ikramah and ‘Alaqamah. A jurist of high calibre, she used to explain the wisdom and background of each tradition that she described. To take a very simple example, she explained that the prescribed bath on a Friday was not just a matter of ritual, as had been maintained by Abu Sa’id al-Khudri and ‘Abdullah ibn ‘Umar, but was meant as practical advice for people who had to travel from far-off places to say their Friday prayers in the Prophet’s mosque.87 While travelling, they perspired and became covered in dust: the Prophet had, therefore, told them to take a bath before attending prayers.88

When the Prophet was preparing to set off for Khaybar to engage in jihad, some women of the Banu Ghifar tribe approached him and said, “O Prophet of God, we want to accompany you on this journey, so that we may tend the injured and help Muslims in every possible way.” The Prophet replied, “May God bless you. You are welcome to come.”89 Umm ‘Atiyah, a Medinan woman, said that she had been present on seven expeditions: “I looked after the emigrants, cooked their food, bound up the wounds of the injured and cared for those who were in distress.”

During the battle with the Jews in Medina, the Muslim women and children were gathered on the roof of a fort with Hassan ibn Thabit as their guard. Safia, the daughter of Abdul Muttalib, who was also present on the roof, describes how she saw a passing Jew taking a round of the fort: “At that time the Banu Qurayza (a Jewish tribe) were doing battle with the Muslims, which is why the road between us and the Prophet was cut off, and there was no one to defend us from the Jews. The Prophet and all his Companions, being on the battlefront, were in no position to come to our assistance. In the meanwhile, the Jew was coming nearer to the fort, and I said, ‘O Hassan, look! This Jew who is walking all around our fort is a danger to us, because he might go and inform the Jews of the insecure position we are in. The Prophet and his Companions are in the thick of battle, so it is your duty to go down and kill him.’ But Hassan replied, ‘By God, you know I am not fit for such a task.’”

At this, she tied a cloth round her waist, picked up a stick, went down to the outside of the fort and beat the man to death. “This done, I came back inside the fort and asked Hassan ibn Thabit to bring the things the Jew had on him, as I, a woman, did not want to touch him. Hassan ibn Thabit replied, ‘Daughter of Abdul Muttalib, I have no need of his possessions.’”90

THE SUCCOR OF GOD

In the sixth year of Hijrah, a 10-year peace treaty was concluded at al-Hudaybiyyah, one article of which specified that anyone emigrating to Muhammad’s camp without the permission of his guardian would have to be returned to Mecca; whereas any Muslim emigrating from Muhammad’s camp to Mecca would not have to be returned.91 This was adhered to in the case of men, one notable instance was that of Suhayl ibn ‘Amr’s son, Abu Jandal, who in spite of having walked 13 miles from Mecca to al-Hudaybiyyah in a badly injured condition with his feet in shackles, was promptly returned to his persecutors. Similarly, other Muslims having managed to free themselves from Quraysh were returned one after another.92 This pact, however, was not regarded as covering the case of Muslim women. This verse of the Quran was revealed on this occasion:

Believers, when believing women seek refuge with you, test them. Allah best knows their faith. If you find them true believers do not return them to the infidels.93

Many incidents have been recorded of women managing to free themselves from the clutches of the Quraysh, coming to Medina, and then not being returned to the Quraysh in spite of the latter invoking the terms of the peace treaty. For example, when Umm Kulthum bint ‘Uqbah ibn Abu Mu’ayt escaped to Medina, she was not returned even when two of her brothers came to take her back.94 The Quraysh considered this refusal a violation of the pact and quickly seized this opportunity to defame the Prophet. It is remarkable, however, that they soon ceased to protest on this score and, considering that they were the Prophet’s direst enemies, it is difficult to understand how this came about. No satisfactory answer is to be found in the books of Sirah and Commentaries on the Quran. Qadi Abu Bakr ibn al-’Arabi writes that the Quraysh ceased to protest because God had miraculously silenced their tongues.95 There can be no doubt about it: it was one of God’s miracles. (Although not in the usual sense of the word).

It is perhaps easier to arrive at the truth by examining the wording of this particular condition of the pact. Here we quote Bukhari’s version, which may be taken as the most authentic: “You will have to return any of our men who come to you, even if they have accepted your faith.”96 The expression “any of our men” (rajul) obviously gave Muslims a loophole by which to exclude women from the application of this condition. This condition of the pact had not been put forward by them, but by the Meccans, and the actual wording had been dictated by the delegates of the Quraysh. It seems that when one of them, called Suhayl ibn ‘Amr, was dictating, he was thinking of both men and women, but that the actual word he chose in order to convey “any person” (inclusive of both men and women) was rajul, which in Arabic is actually used only for men. Most probably this was why the Prophet could legitimately refuse—according to Imam Zuhri—to hand over Umm Kulthum bint ‘Uqbah to her brothers when they came to him to demand her return. Razi is another annalist who records the Prophet on this occasion as having explained that “the condition applied to men and not to women.”97

Thus God, by means of a single word, saved virtuous Muslim women from the humiliation of being returned to their oppressors.

WORKING OUTDOORS

According to ‘Abdullah ibn Mas’ud, when Abu ad-Dahdah, one of the Prophet’s Companions, heard the revelation of this Quranic verse: “Who will give a generous loan to God? He will pay him back two-fold and he shall receive a rich reward,”98 he asked the Prophet, “O Messenger of God, does God want a loan from us?” When the Prophet replied in the affirmative, Abu ad-Dahdah took him by the hand, and said, “I hereby lend my orchard to God.”

Abu ad-Dahdah’s orchard was a sizeable one with six hundred date palms and, at the time he donated it to the cause of Islam, his wife, Umm ad-Dahdah, was staying in it with her children. Nevertheless, having made his pledge to the Prophet, Abu ad-Dahdah came to the orchard, called his wife and told her that she would have to leave, as it had been loaned to God. Umm ad-Dahdah’s reaction was that he had made a good bargain. That is, that God would reward him many times over in the hereafter. So saying, she left the orchard with her children, taking with her all her bags and baggage.99

From this incident we can gather that Umm ad-Dahdah worked on the date orchard. There are many such incidents in the early phase of Islam (the exemplary phase) which show that certainly women were not confined indoors. They certainly went out in order to attend to many necessary outdoor duties. However, one point should be made clear: these outdoor activities of women were not engaged in entertainment but as a matter of necessity. They were meant to build up the family on proper lines and were in no sense intended to establish women’s equality with men in the outside world.

WOMEN’S POSITION

The honorable position accorded by Islam to woman is symbolically demonstrated by the performance of the rite of sa’i, as an important part of the pilgrimage to Mecca, made at least once in a lifetime as a religious duty by all believers who can afford the journey. The rite of sa’i is performed by running back and forth seven times between Safa and Marwah, two hillocks near the Ka’bah. This running, enjoined upon every pilgrim, be they rich or poor, literate or illiterate, Kings or commoners, is in imitation of the desperate quest of Hajar (Hagar), Abraham’s wife, for water to quench the thirst of her crying infant when they arrived in this dry desert country, four thousand years ago, at God’s behest, long before there was any such city as Mecca. (God’s aim in leading Abraham and his wife and child to this barren, inhospitable land was to bring into being a live community which, free of all superstitions and all other corruptions of civilization, would play a revolutionary role led by the last Prophet.) The performance of this rite is a lesson in struggling for the cause of God. It is of the utmost significance that, this was an act first performed by a woman. Perhaps there could be no better demonstration of a woman’s greatness than God’s command to men, literally to follow in her footsteps.

IN THE LIGHT OF EXPERIENCE

The position of women in Islam, as expounded so far in the pages of this book, is a matter neither of conjecture, abstract theory nor of ancient history. Nor is it purely a concept gleaned from readings of the Quran, the Hadith and the history of Islam. It is a matter of actual fact, to which I myself am a witness.

I give the example of the women of my own family who, in times of dire distress, were totally Islamic in their conduct. (I restrict myself to examples taken from my own family, because Islamic precepts do not favor a fuller acquaintance with women outside one’s own family circle). Their nobility of character, under the severest of strains, is something to which I can testify, having seen it with my own eyes. The way in which they have come through certain ordeals in life is a clear proof that, within the limits prescribed by Islam, women can be positively constructive not only within their own domestic sphere, but also much further afield: they can indeed be a powerful and beneficial influence upon others.

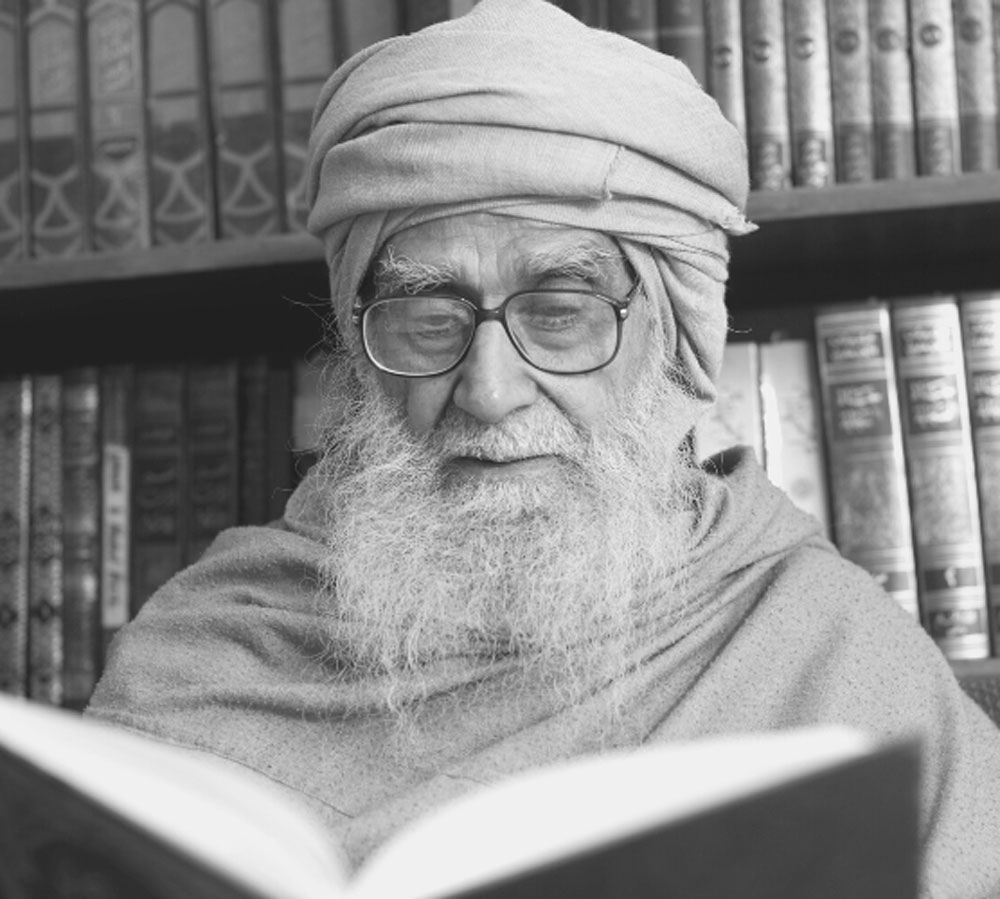

I intend in my autobiography to give a fuller account of these experiences, but here I shall record only such details as are relevant to the role played by my mother. The daughter of Khuda Bux, she was born towards the end of the nineteenth century in the town of Sanjarpur (Azamgarh, U.P., India), and was given the name of Zaibun Nisa. When she passed away in Delhi on 8th of October 1985, she was about 100 years of age. The type of education she had permitted her to read only the Quran and a little Urdu: she was a religious woman in the fullest sense of the word. Never to my knowledge did she tell a lie, or act in a way which could be described as unethical. She was punctual in her prayers and fasting and also had performed Hajj. Spending her entire life in hijab, she was a woman of fine, upstanding character and unbending principle.

My father, Fariduddin Khan, died when I was very young—on December 30, 1929, to be exact. He was the biggest landlord in that part of the country, with lands spread over several villages. One day, on a routine visit to his farm in Newada, he suffered a paralytic stroke, fell unconscious and had to be carried home on a bedstead. There could be no words of final parting, for he passed away the next day without having regained consciousness. My mother, quite suddenly, found herself a widow. I had two brothers and two sisters. My elder brother, ‘Abdul ‘Aziz Khan, was barely 8 years old, I was 5 and my younger brother was just one year old. My sisters were older, but not even in their teens. Both of my sisters died during my mother’s lifetime. By the grace of God my younger brother and I are still alive. My elder brother died in June 1988.

The death of our father at that time was a great blow, not only because we had lost a loving parent, but because of the treatment we received at the hands of certain members of our joint family. After father’s death, these relatives took over the management of the entire family property. My grandfather, under the joint family system, was the person who had actually been entrusted with the management of the farm. But he was so honest that he would not take a single penny more than what was actually required to meet the barest of necessities. After his death, those who then took charge of the orchard exceeded all limits of injustice in their treatment of us. From being landowners of some substance, we suddenly found ourselves landless. There was no easy way out of our problems.

Our family home had been very commodious, but after father’s death, we found ourselves in a disused, half-ruined stable. We lacked even the basic necessities of life and were unable even to find enough money to buy food. At this juncture, people began to advise my mother to remarry, or return to her parents’ home, or go to court to recover the land which was lawfully hers. But mother refused to follow any of this advice. Like the brave Muslim woman that she was, she resolved to face up to those circumstances on her own. This decision was backed up by just two things: faith in God and hard work.

Although my mother’s parents owned a vast tract of land, 20 acres100 of which had been willed to her by her father, she never demanded her share of the land, nor did she seek any help from the members of her family. She depended upon God alone: her sturdy independence was a shining example to us all.

I have seen how she would get up early every morning, say the prescribed prayers and then work right throughout the day without once stopping to rest. When she went to bed, it was always late and only after having said the ‘isha prayer. The tasks on which she spent her entire day included looking after poultry, goats, etc. In this way, I too found the opportunity to graze the goats, a sunnah (practice) of the prophets.

In addition to this work, she voluntarily stitched clothes for people in the neighborhood. Although she did not accept any money for this, her neighbors would send her grain and other comestibles in return for her good offices. This work was by no means easy for her, because it was done in the days before sewing machines had become popular, i.e. she did it entirely by hand. She also managed to keep a buffalo, and in our broad, open courtyard, she grew vegetables and planted fruit trees, like papaya and banana, which gave us a good yield. In those early days of penury, a woman passerby once remarked, “I see you have kittens to look after.” We did indeed look like scraggy little kittens in those days, and if my mother had not made such extraordinary sacrifices in order to look after us, our fate might well have been no better than the little, stray, motherless kittens one sees wasting away in the streets.

My eyes are witness to my mother’s total commitment over a prolonged period to our proper upbringing. But it would really take a whole book to do justice to her, and I have at my disposal just these last few pages.

How straitened were the circumstances in which we were living in those days can be judged by my not even having one paisa to buy a small piece of rubber for a catapult I was making. Hearing of this, one of our acquaintances kindly gave me the money for it. It was galling to think that once having been the biggest landowning family in the area, we had now come to such a sorry pass.

To be quite honest, after our father’s death we had not even the smallest pittance to call our own. The hardships my mother faced at that time are now barely imaginable. It is greatly to her credit that she bore up as well as any man. And from within the confines of the four walls of her home—such as it was—she contrived to influence the external world. She gained the upper hand over her circumstances where such circumstances might well have proved too overwhelming. The most remarkable feature of her attainments, is that she succeeded in achieving, within the limits set for her by Islam, all those objectives for which it is now considered necessary to make women emerge from the Islamic fold—in the process, divesting themselves of their essentially feminine virtues.

Whatever she did, she did in the true spirit of Islam. Instead of turning to man, she turned to God. Instead of thinking in terms of the world, she focussed her attention on the hereafter. All her actions were perfectly in consonance with traditional religious thinking. She had received no such higher education as would have led her to consider the philosophical implications of the course she took. But now, at the mature age of 60, when I look at her strivings through the eyes of a scholar, I see in them the manifestations of human greatness. Even if she had left her home in quest of such higher education as would have fitted her for a post in some secular organization, I do not think she could have done any better for us than she did. Even to imagine her taking such a course of action is quite meaningless.

My mother’s sacrifices made it possible for her not only to give us a satisfactory upbringing, but also to demonstrate what the Islamic bent of mind—positive thinking and a realistic approach—is capable of achieving. My brothers and I were greatly influenced by the example she set. In fact, this was the greatest gift that she could have bestowed upon us. In giving us this awareness of the virtues of Islam, she fulfilled the duties of both father and mother.

I can still recall that after my father’s death, a maternal uncle, Shaikh Abdul Ghafur, used to pay us frequent visits. A great expert in legal matters, he insisted that my mother should file a suit to recover the land which had been willed to her by her father, but which relatives by marriage were unwilling to relinquish. He assured her that all she had to do was to append her signature to the legal documents relevant to her claim on the land and that he would do whatever else was required. He promised her that she would soon have control of all the land of which she was the rightful owner. He continued to pay her visits over a long period of time and went on in the same vein each time, but my mother refused to allow herself to be persuaded by him.

Being deprived of the property from our father’s side, to which we were legally entitled, did, of course become a source of great provocation, and we increasingly felt the urge to fight for our rights. Ultimately, it was through the intervention of others that we were given some tracts of land, but this hardly improved our situation, for, human nature being what it is, it was all the arid and unproductive land which fell to our lot. This niggardly treatment had the effect of making us want to plunge into the fray to do battle with the other party, but my mother staunchly adhered to her policy of patience, often admonishing us to exercise greater self-control. On such occasions she would recite to us this line of poetry:

Patience is the price of eternal paradise.

Our family circumstances which, it appeared, could be improved only by resorting to litigation, were certainly such us to lead us all into negative thinking. Litigation meant a number of families all being drawn into the quarrel, with the inevitable series of unpleasant confrontations. It could even mean the loss of valuable lives, for such situations bring out the most baneful characteristics in all of us. Had our mother not chosen to adopt the only attitude which could be considered positive under the circumstances, we might, at that early formative stage, have fallen prey to unreasoning destructiveness. Each of us would have become permanently tainted by hatred and the desire for revenge.

It was really mother’s single-mindedness in remaining patient that altered the entire course of our lives. She taught us that it would be wrong to fight against those who deprived us of our rights, and inculcated in us the belief that the only course for us to adopt was to improve our lot in life by dint of sheer hard work. She encouraged us to turn our eyes away from what had been denied us and, instead, to give our full attention to that which we still enjoyed, namely, our God-given existence.

Today, my evaluation of this attitude is a rational, conscious process, but in our youth, our positive mental adaptation to negative circumstances was, as it were, an unconscious process stimulated by my mother’s training. This capacity for detachment having become a permanent trait in all of us, we were able to steer clear of confrontations, and chose instead a course of action which should be free of disputes. We three brothers may all have followed different paths, but our basic attitude remained unaltered. That is to say that we studiously ignored the injustice of our immediate environment and endeavored to pursue a morally correct course of action in the broader spectrum of the outside world. If we were deprived by man, we would seek from God. My elder brother, ‘Abdul ‘Aziz Khan, went into business when he grew up, “emigrating” to the town of Azamgarh in 1944. At the outset, he had a long, hard struggle, for he never borrowed, never accepted credit. Only after 40 years of strenuous effort, did he attain the position of Chairman of the Light & Company Ltd., an Allahabad firm which produces electrical goods. From being considered the least important member of our very large family after father’s death, he became its most respected member. He even succeeded in having his share of the family lands restored to him by having the property re-divided in a just manner. The most noteworthy feature of this redistribution is that he caused it to come about without once resorting to litigation.

My younger brother, who opted for scientific studies, received his degree in engineering from the Benaras Hindu University. He later entered the Department of Technical Education run by the Government of Uttar Pradesh, from which he retired as Deputy Director. By virtue of his hard work, faultless character and principled life, he commanded the respect of his whole department.

As for myself, I was interested in religious education, having been initially educated in an Arabic school. I later worked hard to learn the English language and made a thorough study of whatever academic literature was available to me in English. Now, by the grace of God, I am able to work in a positive and constructive manner, as I am sure the readers of my works will confirm.

One special aspect of my work—the call to Muslims to rise above negative thinking and become more positive in their approach—has found an effective vehicle in the AI-Risala monthly which I started in 1976. AI-Risala’s mission has, by the grace of God, assumed the form of a powerful movement all over the Muslim world. I frequently receive oral or written comments from academic circles which acknowledge that AI-Risala’s is the first Islamic movement in Modern times which has attempted to steer Muslims resolutely away from negative activities, and set their feet on the path of positivism.

I thank all those who have been good enough to encourage me; but the real credit for my achievements must go by rights to that devoted Muslim woman called Zaibun Nisa. In this material world of ours, if there is anyone who may be fittingly called the initial founder of this Modern, constructive movement, it is certainly my mother. She had never heard of “Women’s lib,” being very far removed in space, time and culture from such activities, but it is worthy of note that she needed none of the philosophizing of the women’s liberationists to be able to perform what she regarded as her bounden duty in the eyes of God. Whereas my brothers and I set about our tasks in life in a reasoned, conscious manner, for her it was all a matter of instinct, prayer and faith.

I know more than one of my own relatives who, having lost his mother at an early age, became destructive in outlook. We must never underestimate the role of woman as mother. It is perhaps her greatest role in human affairs. In Islamic history, there are numerous examples of the strong and decisive influence of mothers upon their families. A notable example is Maryam Makani, the mother of the Emperor Akbar. When Akbar was harsh in his treatment of Shaikh ‘Abdun Nabi, a great religious scholar of his time, she convinced him of the error he was making, and persuaded him to stop what amounted to persecution.

I cannot but imagine that if I had been deprived of my mother in early childhood, or if I had the kind of mother who kept urging me to fight our “enemies,” my life would have taken an entirely different, and downward course. Undeniably it is the grace of God which has saved me from an ill-fated existence and caused me to become a medium of expression of the truth. But in this world of cause and effect, the human purveyor of God’s will was a lady, a mother, a housewife—one who was Islamic to her very fingertips.

61. The Quran, 4:32.

62. At-Tirmidhi, Sahih, Abwab al-Manaqib, 13/257.

63. Encyclopaedia Britannica (1984), 1/167.

64. Al-Bukhari, Sahih, Kitab Ahadith al-Anbiya’, (Fath al-Bari, 7/104-105).

65. Muslim, Sahih, Kitah Fada’il as-Sahabah, 4/188. FOOTNOTE

66. Al-Haythami, Majma’ az-Zawa’id wa Manba’ al-Fawa’id, Kitab al-Manaqib, 9/224.

67. Ibn Kathir, As-Sirah an-Nahawiyah, 1/386.

68. Ibid., 1/408-409.

69. Ibid., 1/404.

70. Ibid., 1/399.

71. Ibn Sa’d, at-Tabaqat al-Kubra, 8/378-380.

72. The Quran, 58:1.

74. Al-Qurtubi, Al-Jami’ li Ahkamil Quran, 17/269-270.

73. ‘Umayr is a diminutive of ‘ Umar.

75. The animals were to be sacrificed after the performance of Hajj. However, the Quraysh did not allow the Muslims to enter Mecca. The terms of the treaty were humiliating. The Muslims were so disconcerted at not being allowed to make the pilgrimage that they were in no state of mind to follow the Prophet’s command.

76. Ibn Kathir, As-Sirah an-Nabawiyah, 1/386.

77. lbn Majah, Sunan, Al-Muqaddimah 17, 1/81.

78. Sayings and deeds of the Prophet’s Companions.

79. Az-Zarkali, Al-A‘lam (Beirut, 1979), 2/86.

80. Ibn Kathir, As-Sirah an-Nabawiyah, 1/494.

81. Ibn Sa’d, At-Tabaqat al-Kubra, 3/250.

82. The Quran, 39:9.

83. Ibn Kathir, As-Sirah an-Nabawiyyah, 2/236.

84. Bukhari, Sahih, Kitab an-Nikah, (Fath aI-Bari, 9/264-265).

85. The Quran, 9:34.

86. Ibn Kathir, Tafsir, II/352.

87. Ibn Hajar al-’Athqalani, Fath al-Bari fi Sharh al-Bukhari, 2/284-288.

88. Bukhari, Sahih, Kitab al-Jumu’a, 2/307.

89. Ibn Sa’d, Tabaqat al-Kubra, 8/292.

90. Ibn Kathir, AI-Bidayah wa an-Nihayah, 4/108-109.

91. lbn Kathir, As-Sirah an-Nabawiyah, 3/321.

92. Ibid., 3/321-335.

93. The Quran, 60:10.

94. lbn Hajar al-’Athqalani, Fath al-Bari, 7/366.

95. Ahkam al-Quran, Edited by ‘Ali Muhammad al-Bajawi (Beirut, 1987), 4/1786.

96. Bukhari, Sahih, Kitab ash-Shurut fi al-Jihad wa al-Musalah (Fath al-Bari, 5/262).

97. Ibn Hajar al-’Athqalani, Fath al-Bari, 9/34

98. The Quran, 57:11.

99. Ibn Kathir, Tafsir, 4/308.

100. One acre is equivalent to 4840 square yards, or 4047 square meters.