MEDICINE

Just as diseases have afflicted man in every age, so has the science of medicine always existed in one form or the other. In ancient times, however, the science of medicine never reached the heights of progress that it did in the Islamic era and also latterly, in modern times.

It is believed that the beginning of the science of medicine—a beginning to be reckoned with—was made in ancient Greece. The two very great physicians who were born in ancient Greece were Hippocrates and Galen. Hippocrates lived in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. However, very little is known about his life. The historians of later times have estimated that Hippocrates was probably born in 460 B.C. and died in 377 B.C. Some historians, on the other hand, even have doubts about his being a historical figure. It has also been questioned whether the books on philosophy and medicine supposedly written by him were not actually written by someone else and later attributed to him.

Galen is considered the second most important philosopher and physicist of this period of antiquity. He was born probably in A.D. 129 and died in A.D. 199. Galen had to face stiff opposition in Rome, and most of his writings were destroyed. The remainder would also have been lost to posterity if the Arabs had not collected them in the ninth century and translated them into Arabic. These Arabic translations were later to reach Europe, in the eleventh century, where they were translated from Arabic into Latin. The Encyclopaedia Britannica (1984) concludes its article on Galen: “Little is known of Galen’s final years.”

It is a fact that ancient Greece produced some very fine brains and some very high thinking in this field. But the respective fates of Galen and Hippocrates show that the atmosphere in ancient Greece was conducive neither to the rise of such people to their due eminence, nor to the growth of medicine as a science. Different kinds of superstitious beliefs were an obstruction in the path of free enquiry; for instance, the attribution of diseases to mysterious powers, and the sanctification of many things, such as plants, which had healing properties.

The science of medicine came into being in ancient Greece about 200 years before the Christian era and flourished for another two centuries. In this way, the whole period extended over about four or five hundred years. This science did not see any subsequent advance in Greece itself. Although a European country, Greece did not contribute anything to the spread of its own medical science in Europe, or to modern medicine in the West. These facts are proof that the atmosphere in ancient Greece was not favourable to the progress of medicine.

The Greek medicine which was brought into being by certain individuals (effort was all at the individual level, as the community did not give it general recognition) remained hidden away in obscure books for about one thousand years after its birth. It was only when these books were translated into Arabic during the Abbasid period (750-1258), and edited by the Arabs with their own original additions, that it became possible for this science to find its way to Europe, thus paving the way for modern medical science.

The reason for this is that before the Islamic revolution, the world had been swept by superstitious beliefs and idolatry. The environment in those times was so unfavourable that whenever an individual undertook any academic or scientific research, he could never be certain of receiving encouragement. More often than not, he had to face severe antagonism. Indeed, whenever any scientific endeavour at the individual level came to the notice of the authorities, it would be promptly and rigorously suppressed. In a situation where diseases and their remedies were traditionally linked with gods and goddesses, what appeal could the scientific method of treatment have for the people? Only when the monotheistic revolution came to the world in the wake of Islam did the door open to that medical progress which saw its culmination in modern medical science.

As the Prophet said, “God has sent the remedy for every disease in the world except death.” (Mustadrak al-Hakim, Hadith No. 8220) This saying of the Prophet was the declaration of the leader of a revolution. No sooner did he announce to the world this truth about medicine than history began to be shaped by it in many practical ways.

AN EXAMPLE

Smallpox is considered one of the most dangerous diseases in the world. It is a highly contagious disease, characterised by fever and the appearance of small spots leaving scars in the form of pits. The symptoms include chill, headache, and backache. The spots appear around the fourth day. This is a fatal disease. Even if one survives the attack, the skin is scarred permanently.

According to present records, this disease was identified in Egypt in 1122 B.C. and is also mentioned in ancient Indian books written in Sanskrit. In the past this disease gripped many countries in the form of dangerous epidemics. Thousands of people fell prey to it. As far back as 1156 B.C. this disease was taking its toll of human life, there being visible evidence in the pock-marked face of the mummy of the Egyptian Pharaoh, Ramses V, who died in that year. (His embalmed body was found inside a pyramid.) Even then, it took thousands of years for this dreaded disease to be investigated scientifically.

Now we know that smallpox is a contagious disease resulting from virus infection, and such remedies have been discovered as can ward off attacks, provided suitable precautions are taken in advance.

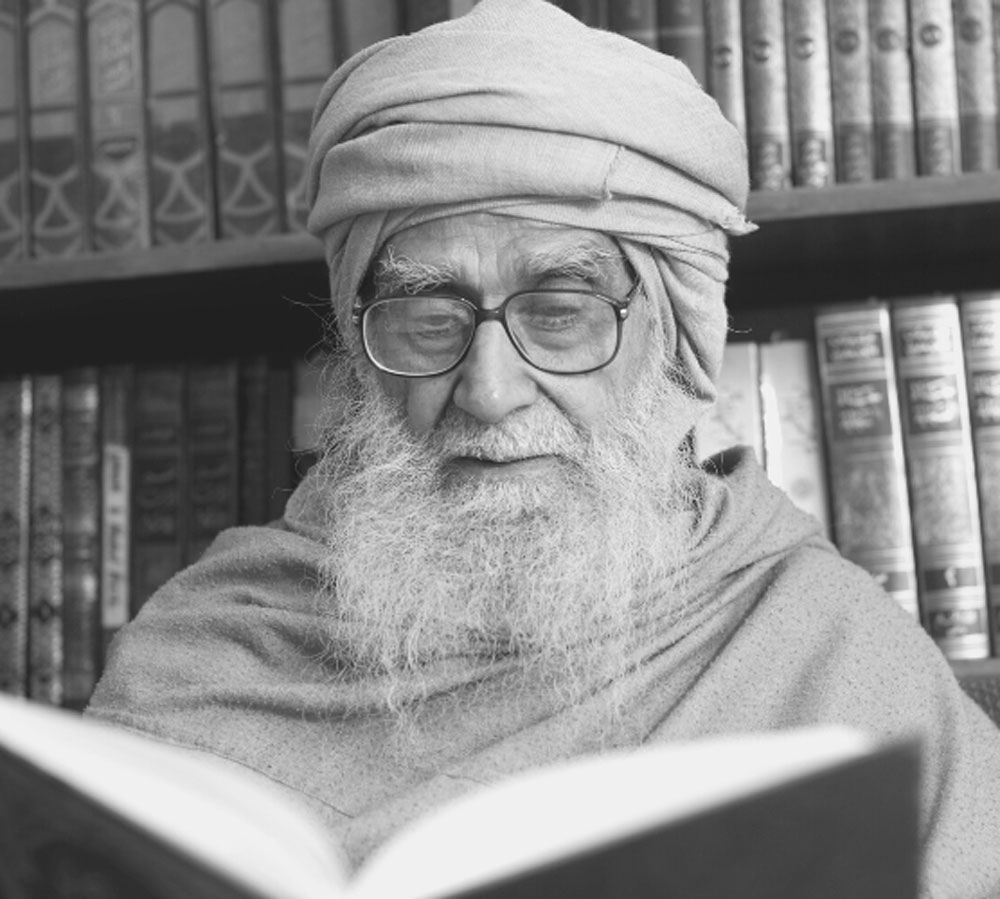

But it was not until the end of the ninth century, subsequent• to the emergence of Islam, that this medical fact was unearthed for the first time. The first name, which became prominent in history in this connection was that of the well-known Arab physician, Al-Razi (865-925), who was born in Ray in Iran. In search of a remedy for the disease, he investigated it from the purely medical standpoint and wrote the first book on the subject, called, Al-Judri wa al-Hasba. This was translated into Latin, the academic language of ancient Europe, in 1565 in Venice. It was later translated into Greek and other European languages, and thus spread all over Europe. Its English translation, published in London in 1848, was entitled, A Treatise on Smallpox and Measles.

Researchers have accepted that this is the first medical book on smallpox in the whole of recorded history. Prior to this, no one had ever done research on this topic.

After reading Al-Razi’s book, Edward Jenner (1749-1823), the English physician who became the inventor of vaccination, was led to making a clinical investigation of the disease. He carried on his research over a twenty-year period, ultimately establishing the connection between cowpox and smallpox. In 1796, he carried out his first practical experiment in inoculation. This was a success, and the practice spread rapidly, in spite of violent opposition from certain quarters, until, in 1977, it was announced by the UN that for the first time in history, smallpox had been eradicated.

Now the question arises as to why such a long time had elapsed between the initial discovery of the disease and the first attempts to investigate it medically with a view to finding a remedy. The reason was the prevalence of shirk, that is, the holding of something to be sacred when it is not, or the attribution of divinity to the non-divine.

Dr. David Werner writes, ‘In most places in India, people believe that these diseases are caused because the goddess is angry with their family or their community. The goddess expresses her anger through the diseases. The people believe that the only hope of a cure for these diseases is to make offerings to her in order to please her. They do not feed the sick child or care for him because they fear this will annoy the goddess more. So the sick child becomes very weak and either dies or takes a long time to get cured. These diseases are caused by virus infection. It is essential that the child be given plenty of food to keep up his strength so that he can fight the infection.’

When Islam came to the world, it banished such superstitious beliefs about disease, announcing in no uncertain terms that none except God had the power to harm or benefit mankind. The Creator was the one and only being who had such power. All the rest were His creatures and His slaves. When, after the Islamic revolution, such ideas gained ground, people began to think freely and independently of all superstitions. Only then did it become possible to conduct medical research into disease in order to discover appropriate remedies.

Only after this intellectual revolution had come to the world did it become possible to make smallpox the subject of enquiry. Only then did it become possible for such people as Abu Bakr Razi and Edward Jenner to rise and save the world from this dreaded disease by discovering a remedy for it.

The real barrier to finding a cure was the generally accepted body of superstitious beliefs based on idol worship; these beliefs were swept away for the first time in history by Islam.