HISTORIOGRAPHY

The starting point in Arnold Toynbee’s philosophy of history was his contention that the proper unit of historical study must be a civilization, rather than the traditional unit, the nation state.

Both these concepts, however, hinge on the same principle: that history should not focus solely on royal actions and prerogatives throughout the ages, but should be a study of the sum of all activities of all groups of human beings, whatever the framework, political or civilizational, within which they interact. In the long history of mankind, this approach, developed only during the last few centuries, is relatively new. History, or historiography, is now equated with ‘man-story’ as opposed to the ‘King-story’ of the pre-modern era. ‘King-story,’ made up of elaborate descriptions of kings, along with copious details of the palaces they occupied and the generals they commanded, had made no mention of the common man, even if his achievements were marked by greatness. The only man considered worthy of mention was the one whose head was adorned by a crown. Ancient history thus amounted to a belittling of humanity in general.

While real events relating to non-kings were regarded as undeserving of any mention, even legendary tales and concocted stories about the kings were preserved in writing as if they were great realities. Take, for instance, the building of Alexandria, the renowned coastal city named after its founder, Alexander the Great. Many strange stories are associated with the foundation of this city. One of them concerns sea genies who were said to have put obstacles in the path of building when the work was first started. Alexander, so the story goes, decided to see for himself what the genies were about. He gave orders for a large box of wood and glass to be made, and when it was ready, he had himself lowered in it to the bottom of the sea. There he drew pictures of the genies and then back on land, he had metal statues cast to look exactly like the dragons. These statues were then laid under the foundations of Alexandria. When the sea genies came there and saw that genies like themselves had been killed and buried in the foundations, they became frightened and ran away. The fact that this tale gained currency shows the credulous state in which the whole world lived before the advent of Islam.

In old historical records, the most striking omissions are the lives and influence of the great prophets of the world. Today people would find it very strange if a history of the freedom struggle of India laid no stress on the role of Gandhiji, or if a history of the erstwhile U.S.S.R. omitted Lenin altogether. But a far strange history is one bereft of all mention of those pious souls, who were the messengers of God. The sole exception to this rule of omission is the Final Prophet, Prophet Muhammad. The reason for his prominent inclusion in historical records is that, by setting in motion the Islamic revolution, he was able to change exactly those factors—the undemocratic, polytheistic and superstitious nature of society—which in the past had been responsible for such astonishing lacunae in the writing of human history. There can be no doubt that it was the Islamic revolution which made it possible for historiography to proceed on scientific lines.

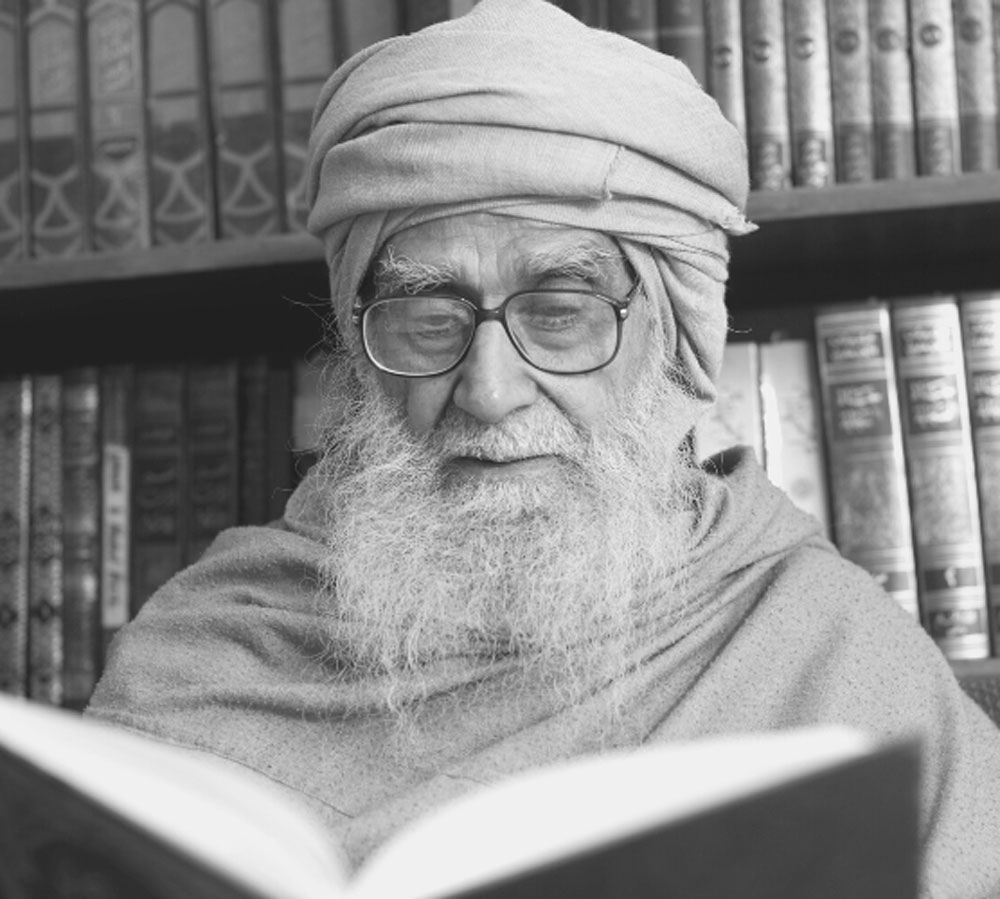

In known human history, Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) is the only historian to have changed the pattern of historiography. It was he who raised historiography from the level of mere King-story to the level of genuine man-story. “Kingology” was changed into sociology. The truth is that the science known today as sociology is the gift of Ibn Khaldun. He himself claimed that he was the founder of sociology, and there is no reason to dispute his claim.

Khaldun’s greatness was acknowledged in a similar vein by Robert Flint: “As a theorist on history he had no equal in any age or country until Vico appeared, more than three hundred years later; Plato, Aristotle and Augustine were not his peers.”

It was indeed Ibn Khaldun who gave to Europe the modern science of history. And it was Islam, which bestowed this gift upon him. The Islamic revolution produced Ibn Khaldun and Ibn Khaldun produced the modern science of history.

Professor Philip K. Hitti writes:

The fame of Ibn-Khaldun rests on his Muqaddama (Introduction to his book on history). In it he presented for the first time a theory of historical development which takes due cognizance of the physical facts of climate and geography as well as of the moral and spiritual forces at work. As one who endeavoured to formulate laws of national progress and decay, Ibn Khaldun may be considered the discoverer—as he himself claimed—of the true scope and nature of history, or at least the real founder of the science of sociology. No Arab writer, indeed no European, had ever taken a view of history at once so comprehensive and philosophic. By the consensus of critical opinion Ibn-Khaldun was the greatest historical philosopher Islam produced, and one of the greatest of all time.

In Book I of the Muqaddamah, Ibn Khaldun sketches a general sociology; in Books II and III, a sociology of politics; in Book IV a sociology of urban life; in Book V, a sociology of economics; and in Book VI, a sociology of knowledge. The work is studded with brilliant observations on historiography, economics, politics, and education. It is held together by his central concept of asabiyah, or social cohesion. Thus he laid the foundation of a science of history which is not based just on the description of kings, but which is, in a vaster sense, based on the economics, politics, education, religion, ethics, and culture of the whole nation.

Historians have generally acknowledged that the science of history remained undeveloped before the emergence of Ibn Khaldun, and that he was the first person to develop a philosophy of history. The Encyclopaedia Britannica even goes so far as to say that “he developed one of the world’s most significant philosophies of history.”

The question arises as to how it became possible for Ibn Khaldun to discover something, which had remained undiscovered for centuries. The answer is that other historians were born before the Islamic revolution, while Ibn Khaldun was born after it. On the basis of monotheism, Islam had brought about a revolution, which eliminated the difference between King and commoner. All human beings, the offspring of Adam and Eve, were held to be equal. It was, uniquely, this great revolution of equality that paved the way for an Ibn Khaldun—himself a product: of this revolution—to lay the foundation of modern history in which the central position was held not by ‘royal figures’ but by humanity itself.

One belief which had hampered the development of the science or art of history was polytheism. The whole period prior to Islam was pervaded by polytheistic beliefs, which were supportive of divine kingship. “The King has often stood as mediator between his people and their god, or as the god’s representative.” Some kings pretended to be incarnations of God, or even gods themselves, without feeling the need to rationalize their claims. They did so in order that by the ‘divine right of kings,’ their absolute sovereignty should never be questioned. Even where monarchs made no such claims, they were credited with divinity, because divinity was universally associated with kings. Whenever the common people came upon anything that was out of the ordinary, they regarded it as supernatural and, if it was a person, they took him to be a god, or a manifestation of a god. Naturally, this mentality was not discouraged by the kings.

The ancient rulers, on the contrary, encouraged such superstitious notions so that people would continue to regard them as superior beings. In known history, the Prophet Muhammad was the first ruler who refuted such superstitious beliefs, showing them to be without foundation. In this way, he led mankind along the path of enlightenment, eliminating the differences between men on an intellectual plane. He held as baseless all those suppositions and superstitions which had been responsible for creating and perpetuating the slave-master mentality.

Towards the end of the Prophet Muhammad’s life, Maria Qibtiya bore him a beautiful and vivacious son in Medina. The Prophet named him Ibrahim, after the Prophet Abraham (May peace be upon him). Ibrahim was just one and a half years old when, in the tenth year of Hijrah (January 632 A.D.), he died. It so happened that the death of Ibrahim coincided with a solar eclipse. From ancient times, one of the many prevailing superstitions was that the solar and lunar eclipses were caused by the death of some king or other important personage. They were meant to show, they thought, that the heavens mourned the death of the exalted in station. At that time, Prophet Muhammad was King of Arabia. For this reason, certain of the Medinans began attributing the eclipse to the death of the Prophet’s son. As soon as the Prophet heard of this, he refuted it. There are several accounts of this incident in the books of Hadith. One of these was recorded as follows:

One day the Prophet came in great haste to the mosque. At that time the sun was in eclipse. The Prophet began to say his prayers and, by the time he had finished, the eclipse was over. Then, addressing the congregation, he said that people imagined that the, sun and moon went into eclipse at the death of some important person, but that this was not true. The eclipses of the sun and moon were not due to the death of any human being. Both the sun and the moon were just two of God’s creations; with which He did as He willed. He told them that when they saw an eclipse, they should pray to God.

When the whole of Arabia had come under the domination of Islam, the Prophet made a farewell Hajj pilgrimage in his last days, along with 1,25,000 companions. During this pilgrimage he delivered his historic sermon on the plain of Arafat, which is known as Khutba Hajjatul Wida, the sermon of the farewell pilgrimage.

This sermon was a declaration of human rights: “Hear, O people. All human beings are born of a man and a woman. All the apparent differences are only for the sake of introduction and identification. The most worthy before God is the one who is the most God-fearing. No Arab has any superiority over a non-Arab and vice versa. No black has any superiority over a white and vice versa. Taqwa (piety) is the only thing which will determine one’s superiority over others.” (Musnad Ahmad, Hadith No. 23489) To this the Prophet added, “All things of the period of ignorance before Islam have been trampled down by my steps.” (Seerah Ibn Kathir, vol. 4, p. 340) For the first time in ancient history, all sorts of inequality and discrimination were almost entirely elimi-nated.

Only then did a new civilization come into being in which all human beings were equal. Speaking of the successors of the Prophet, Abu Bakr and ‘Umar, Mahatma Gandhi noted, “though they were masters of a vast empire, they lived the life of paupers.”

This revolution was so powerful that even at a later period, when the rot had set in in the institutions of governments, and the Caliphs had been replaced by “emperors,” the pressure of Islamic civilization was so great that none of these emperors” could live in the style of the ancient monarchs. In Islamic history there are many such instances. The following incident, which took place during the reign of Sultan Abdur Rahman II (A.D. 176-258), a powerful ruler of Muslim Spain, is an apt illustration.

This Sultan had a palace built for himself called az-Zahra, to the east of Cordova, which was of such immensity that the word palace was not adequate to describe it. This magnificent residence came to be known as al-Madinah az Zahirah (the brilliant town). But, in spite of being so powerful and living in such magnificence, the Sultan did not regard himself as being above the law.

It happened once that he missed one fast in the month of Ramazan without having any excuse, which would be acceptable in terms of the shariah. He therefore assembled the ‘ulama (religious scholars) of Cordova and told them of his lapse. He asked them to pronounce a religious verdict, which would enable him to atone for it.

Al-Maqqari writes that one of the religious scholars present was Imam Yahya, who promptly decreed that the King should observe 60 continuous fasts in expiation. On leaving the palace, he was asked by one of the ‘Ulama why he had insisted on such a severe form of punishment when the shariah offered the alternative of feeding 60 poor people in atonement for one missed fast. Why had he not instructed the King to feed 60 poor people instead of requiring him to fast himself?

Angered by this question, Imam Yahya replied, “For a king to feed 60 poor people is no punishment.” As we learn from the annals of Andalusion history, Sultan Abdur Rahman II did accept the fatwa (verdict) of Imam Yahya, and did observe 60 continuous fasts. He showed no reaction whatsoever. He did not even dismiss Imam Yahya from his office.

This can be explained in terms of the impact of the Islamic revolution, which had put an end to the difference between a subject and a ruler. It had created such an atmosphere of human equality, that no one could regard himself as being superior to others. Not even a king dared to set himself apart from the commoners or to flout the law.

Before the Islamic revolution it was an accepted fact that the king was superior to a common man. For instance, the Byzantine emperor, Heraclius, a contemporary of Prophet Muhammad, in spite of being a Christian, “had married his niece, Martina,—thus offending the religious scruples of many of his subjects, who viewed his second marriage as incestuous.”

It was known to the people that this marriage was illegal, yet there was no public outcry. This was because Heraclius was a king and, therefore, above any judgement by human standards. As a king, he had the right to do as he pleased.

In ancient times, this extraordinary concept of the greatness of kings was so firmly implanted, as a matter of superstitious belief that ordinary citizens had begun to consider their monarchs to be innately superior creatures. The observance of special rites and rituals by kings was aimed at reinforcing this way of thinking. The kings had thus, in their respective empires, achieved a temporal greatness, which was on a parallel with God’s prerogative in the vastness of His universe. It was but natural that historiog-raphy should come under the influence of this concept of the ‘divine right of the kings’ so that, in practice, it became a chronicle of the lives of royal families with scant reference to the common man.

With the onset of the Islamic revolution in Arabia and neighbouring countries, objects of nature like the sun and moon were dislodged from their divine pedestals. In link manner, kings were removed from the seat of extraordinary greatness. Now a king was just a human being like any other.

The influence of the Islamic revolution, which ultimately reached Asia, Africa and many European countries, paved the way for a new atmosphere on a universal scale. With the new way of thinking, the old king-centered mentality gave way to a man-centered ethos. Prominent expression was given to a new approach to historiography in the writings of Abdur Rahman Ibn Khaldun, who in the foreword to his Kitab al-Ibar, propounded his theory of how history should be written. This foreword, or Muqaddamah, is considered so important that it has been published many times in several languages.

The most eminent of the Mamluk historians was al-Maqrizi, a disciple of Ibn Khaldun. It was through him in the fifteenth century that Ibn Khaldun’s theories were introduced into Egypt. Later, other Muslim countries came under their influence. Between 1860 and 1870 a complete rendering of the Muqaddamah was published in French, thus introducing his historical theories into Europe. These thoughts took root in the soil of Europe and gained great popularity. Vico and other western historians developed this art, finally giving rise to the modern form of historiography.