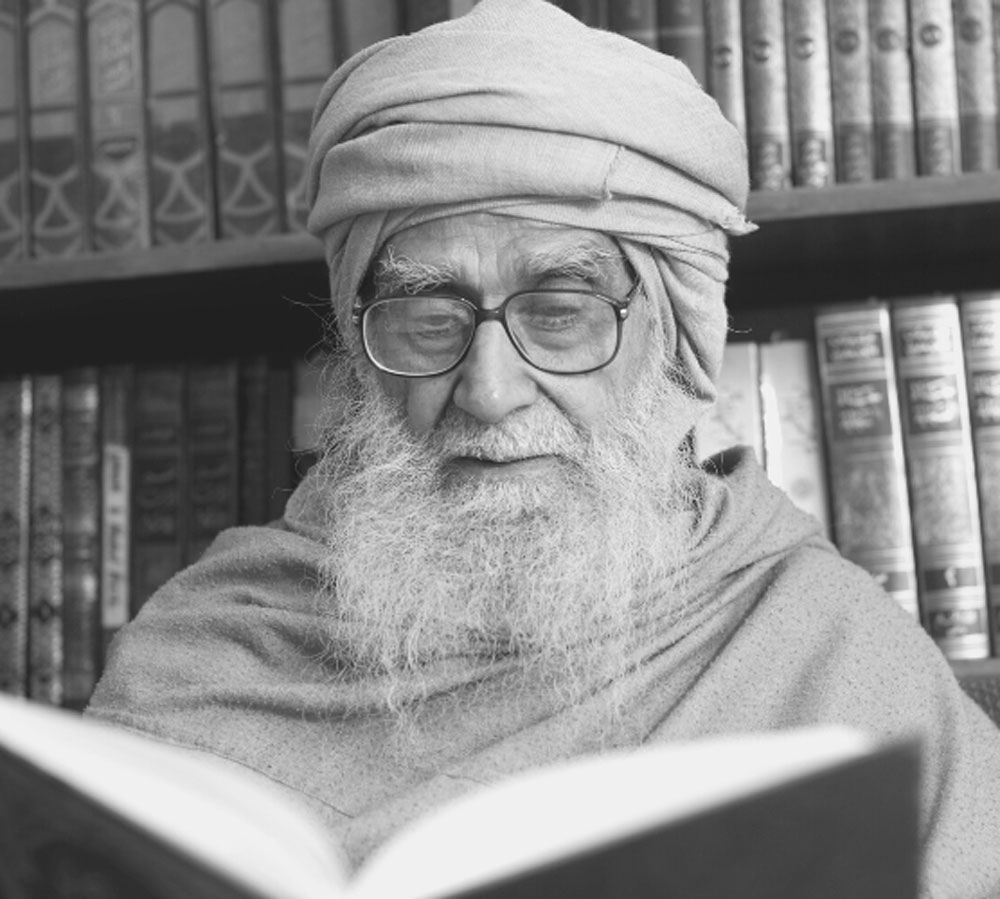

The Prophet of Islam, Muhammad, upon whom be peace, was born in Arabia on 22 April A.D. 570, and died on 8 June A.D. 632. He was a very handsome and powerfully built man. His childhood gave indications of the sublime and dynamic personality that was to emerge. As he grew up, the nobility of his personality used to have an effect on anyone beholding him, but he was so soft-spoken and of such genial disposition that anyone coming into close contact with him would learn to love him. A perfectly balanced personality—tolerant, truthful, perspicacious and magnanimous—he presented the highest example of human nobility. According to Daud ibn Husayn, he became known as he grew older as the most chivalrous among his people, tolerant and forebearing, truthful and trustworthy, always the good neighbour. He would stay aloof from all quarrels and quibbles and never indulged in foul utterances, abuse or invective. People even left their valuables in his custody, for they knew that he would never betray them. His unimpeachable trustworthiness won for him the title of “al-Amin,” a faithful custodian, an unfailing trustee.

When he married at the age of twenty-five, his uncle Abu Talib performed the marriage service. “There is no one to compare with my nephew, Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullah,” he said. “He outshines everyone in nobility, gentility, eminence and wisdom. By God, he has a great future and will reach a very high station.” Abu Talib did not utter these words in the sense in which later events proved them to be true. He meant them in a worldly sense. Nature had endowed his nephew with a magnetic and versatile personality. His people would surely appreciate his qualities, and raise him to a high position. Abu Talib envisaged a future of worldly success and accomplishment for his nephew; this was the “great future” which he referred to in his sermon.

Without doubt the Prophet had every opportunity for worldly advancement. He was born into a noble family of Makkah and his virtues guaranteed his success in life. True, he had inherited just one camel and one servant from his father, but his inborn high qualities had impressed the richest woman in Makkah, Khadijah, a forty-year-old widow belonging to a family of merchants. When the Prophet was twenty-five, she offered herself to him in marriage. Not only did marriage with Khadijah provide the Prophet with wealth and property; it also threw open to him a vast field of business in Arabia and beyond. The Prophet had every opportunity, then, of leading a successful and comfortable life. But he forsook all these things and chose something quite different for himself. Quite intentionally, he took a road that could lead only to worldly ruin. Before his marriage, the Prophet had earned his living in different ways. Now he relinquished all such activity, and dedicated himself to his lifelong vocation—the pursuit of truth. He used to sit for hours and ponder over the mysteries of creation. Instead of socializing and trying to gain a position for himself among the nobles of Makkah, he would wander in the hills and dales of the desert. Often he used to retire to the loneliness of a cave in Mount Hira’—three miles from Makkah—and stay there until his meagre supply of food and water was exhausted. He would return home to replenish his supplies, and then go back to the solitude of nature for prayer and meditation. He would beseech the Maker of the heavens and the earth for answers to the questions surging in his mind. What is our true role in life? What does the Lord require of us, as His servants? Whence do we come and whither will we go after death? Unable to find answers to these questions in the centres of human activity, he betook himself to the stillness of the desert; perhaps, there, the answer would be forthcoming.

The Romanian orientalist Konstan Virgil George (b. 1916) writes in his book, The Prophet of Islam: Until one has spent some time in the wilds of Arabia and the Middle East, one cannot begin to understand how the vastness and tranquility of the desert expands the human intellect and fortifies the imagination. There is a great difference between European and Arabian plants. There is no plant in the arid reaches of the desert that does not exude a sweet fragrance; even the acacia trees of this land are aromatic. The desert stretches for 3,000,000 square kilometres. Here it is as though man comes into direct contact with God. Other countries are like buildings in which massive walls obstruct one’s view; but there is nothing blocking one’s vision of reality in the vast open reaches of Arabia. Wherever one looks, one sees endless sands and fathomless sky. Here, there is nothing to stop one from consorting with God and His angels.1

It was no small matter that a young man should be taking up this course in the prime of his life. He was renouncing worldly happiness and choosing a way fraught with difficulties and sorrow. He had all conceivable means and opportunities for a comfortable life, but his turbulent soul did not find satisfaction in them. He attached no value to them and could not rest content until he had unravelled the mysteries of life. He sought to delve beyond external appearances, and seek out the reality of life. Worldly gain and loss, comfort and distress, did not concern him; what mattered to him was the all-important question of truth and falsehood.

This phase of the Prophet’s life is referred to thus in the Quran: Did he not find you wandering and guide you?2

The word used in this verse for “wandering” (“dhallan”) can also be used to describe a tree standing alone in an empty desert. The Prophet, then, was like a lone tree standing amidst the vast wilderness of ignorance that was Arabia of the time. The idea of consolidating his position in this society was abhorrent to him. He sought the truth, and nothing less than the truth could satisfy his soul. His quest had reached a point when life had become an unbearable burden. The Quran looks back on that time:

Have We not lifted up and expanded your heart and relieved you of the burden, which weighed down your back?3

God, indeed, relieved him of his burden. He turned in mercy to His Prophet, illuminating his path and guiding him on his journey. On February 12, A.D. 610, the Prophet was sitting alone in his cave. The angel of the Lord appeared before him in human form and taught him the words, which appear at the beginning of the ninety-sixth chapter of the Quran. The Prophet’s quest had finally been rewarded. His restless soul had joined in communion with the Lord. Not only did God grant him guidance; He also chose Muhammad as His Prophet and special envoy to the world. The mission of the Prophet extended over the next twenty-three years. During this period the entire content of the Quran—the final divine scripture —was revealed to him.

The Prophet of Islam discovered Truth in the fortieth year of his arduous life. If was an attainment that was not to usher in ease and comfort, for this Truth was that he stood face to face with an Almighty God. It was discovery of his own helplessness before the might of God, of his own nothingness before the supernatural magnitude of the almighty. With this discovery it became clear that God’s faithful servant had nothing but responsibilities in this world; he had no rights.

The meaning that life took on for the Prophet after the Truth came to him can be ascertained from these words: Nine things the Lord has commanded me. Fear of God in private and in public; Justness, whether in anger or in calmness; Moderation in both poverty and affluence; That I should join hands with those who break away from me; and give to those who deprive me; and forgive those who wrong me; and that my silence should be meditation; and my words remembrance of God; and my vision keen observation.4

These were no just glib words; they were a reflection of the Prophet’s very life. Poignant and wondrously effective words of this nature could not emanate from an empty soul; they themselves indicate the status of the speaker; they are an outpouring of his inner being, an unquenchable spirit revealed in verbal form.

Even before the dawn of his prophethood, the Prophet’s life had followed the same pattern. The motivation, however, had been subconscious; now it came on to the level of consciousness. Actions which had previously been based on instinctive impulses now became the well-conceived results of profound thinking. This is the state of one who reduces material needs to a minimum; whose life assumes a unique pattern; who in body lives in this world, but in spirit dwells on another plane.

The Prophet once said, A discerning person should have some special moments: a moment of communion with God; a moment of self-examination; a moment of reflection over the mysteries of creation; and a moment which he puts aside for eating and drinking.5

In other words, this is how God’s faithful servant passes the day. Sometimes the yearning of his soul brings him so close to God that he finds something in communion with the Lord. Sometimes fear of the day when he will be brought before the Lord for reckoning makes him reckon with himself. Sometimes he is so overawed by the marvels of God’s creation that he starts seeing the splendours of the Creator reflected therein. Thus he spends his time encountering the Lord, his own self, and the world around him, while also finding time to cater for his physical needs.

These words are not a description of some remote being; they are a reflection of the Prophet’s own personality, a flash from the light of faith that illuminated his own heart. These “moments” were an integral part of the Prophet’s life. One who has not experienced these states can never describe them in such a lofty manner. The soul from which these words emanated was itself in the state that they describe; through words that state of spiritual perfection was communicated to others.

Before he received the word of God, this world—with all its shortcomings and limitations—appeared meaningless to the Prophet. But now that God had revealed to him that besides this world there was another perfect and eternal world, which was the real abode of man, life and the universe took on new meaning. He now found a level on which his soul could subsist, a life in which he could involve himself, heart and soul. The Prophet now found a real world into which he could put his heart and soul, a target for all his hopes and aspirations, a goal for all his life’s endeavours.

This reality is discovered not merely on an intellectual level. When it takes root, it transforms one completely, and raises one’s level of existence. The Prophet of Islam provides us with a superlative example of this way of life. The greatest lesson imparted by his life is that, unless one changes one’s plane of existence, one cannot change one’s plane of actions.

When the Prophet Muhammad discovered the reality of the world hereafter, it came to dominate his whole life. He himself became most desirous of the Heaven of which he gave tidings to others, and he himself was most fearful of the Hell of which he warned others. Deep concern for the life to come was always welling up inside him. Sometimes it would surge to his lips in the form of supplication, and sometimes in the form of heartfelt contrition. He lived on a completely different plane from that of ordinary human beings. This is illustrated by many incidents a few of which are mentioned here.

Once the Prophet was at home with Umm Salamah. He called the maid-servant, who took some time in coming. Seeing signs of anger on the Prophet’s face, Umm Salamah went to the window and saw that the maid was playing. When she came, the Prophet had a miswak6 in his hand. “If it wasn’t for the fear of retribution on the Day of Judgement,” he told the maid, “I would have hit you with this miswak.” Even this mildest of punishments was to be eschewed.

The men taken prisoner in the Battle of Badr were the Prophet’s bitterest enemies, but still his treatment of them was impeccable. One of these prisoners was a man by the name of Suhayl ibn ‘Amr. A fiery speaker, he used to denounce the Prophet virulently in public to incite people against him and his mission. ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab suggested that two of his lower teeth be pulled out to dampen his oratorical zeal. The Prophet was shocked by ‘Umar’s suggestion. “God would disfigure me for this on the Day of Judgement, even though I am His messenger,” he said to ‘Umar.

This is what is meant by the world being a planting ground for the hereafter. One who realizes this fact lives a life oriented towards the hereafter—a life in which all efforts are aimed at achieving success in the next, eternal world; a life in which real value is attached—not to this ephemeral world—but to the life beyond death. One becomes aware that this world is not the final destination; it is only a road towards the destination, a starting-point of preparation for the future life. Just as every action of a worldly person is performed with worldly interests in mind, so every action of God’s faithful servant is focused on the hereafter. Their reactions to every situation in life reflect this attitude of looking at every matter in the perspective of the life after death, and of how it will affect their interests in the next world. Whether it be an occasion of happiness or sorrow, success or failure, domination or depression, praise or condemnation, love or anger—in every state they are guided by thoughts of the hereafter, until finally these thoughts become a part of their unconscious minds. They do not cease to be mortal, but their minds come to function only on matters related to the world of immortality, making them almost forget their interest in worldly matters.

Humility And Forbearance

The Prophet was a man like other men. Joyous things would please him while sad things would sadden him. Realization of the fact that he was first and foremost God’s servant, however, prevented him from placing more importance on his own feelings than upon the will of God.

Towards the end of the Prophet’s life Mariah Qibtiyah bore him a beautiful and vivacious son. The Prophet named him Ibrahim, after his most illustrious ancestor. It was Abu Rafi’ who broke the good news to the Prophet. He was so overjoyed that he presented Abu Rafi’ with a slave. He used to take the child in his lap and play with him fondly. According to Arab custom, Ibrahim was given to a wet nurse, Umm Burdah bint al-Mundhir ibn Zayd Ansari, to be breast-fed. She was the wife of a blacksmith, and her small house was usually full of smoke. Still, the Prophet used to go to the blacksmith’s house to visit his son, putting up in spite of his delicate disposition—with the smoke that used to fill his eyes and nostrils. Ibrahim, was just one and half years old when, in the tenth year of the Hijrah (January A.D. 632), he died. The Prophet wept on the death of his only son, as any father would: on this respect the Prophet appears like any other human being. His happiness and his grief were that of a normal father. But with all that, he fixed his heart firmly on the will of God. Even in his grief, these were the words he uttered:

God knows, Ibrahim, how we sorrow at your parting. The eye weeps and the heart grieves, but we will say nothing that may displease the Lord.

It so happened that the death of Ibrahim coincided with a solar eclipse. From ancient times people had believed that solar and lunar eclipses were caused by the death of some important person. The people of Madinah began attributing the eclipse to the death of the Prophet’s son. This caused the Prophet immense displeasure, for it suggested this predictable astronomical event was caused out of respect for his infant son. He collected the people and addressed them as follows:

Eclipses of the sun and moon are not due to the death of any human being; they are just two of God’s signs. When you see an eclipse, then you should pray to God.

On one of his journeys, the Prophet asked his companions to roast a goat. One volunteered to slaughter the animal, another to skin it, and another to cook it. The Prophet said that he would collect wood. “Messenger of God,” his companions protested, “we will do all the work.” “I know that you will do it,” the Prophet replied, “but that would amount to discrimination, which I don’t approve of. God does not like His servants to assert any superiority over their companions.”

So humble was the Prophet himself that he once said: By God, I really do not know, even though I am God’s messenger, what will become of me and what will become of you.7

One day Abu Dharr al-Ghifari was sitting next to a Muslim who was black. Abu Dharr addressed him as “black man.” The Prophet was very displeased on hearing this, and told Abu Dharr to make amends “Whites are not superior to blacks,” he added. As soon as the Prophet admonished him, Abu Dharr became conscious of his error. He cast himself to the ground in remorse, and said to the person he had offended: “Stand up, and rub your feet on my face.”

The Prophet once saw a wealthy Muslim gathering up his loose garment to maintain a distance from a poor Muslim sitting next to him. “Are you scared of his poverty clinging to you?” the Prophet remarked.

Once the Prophet had to borrow some money from a Jew by the name of Zayd ibn Sa’nah. A few days before the date fixed for the repayment of the debt, the Jew came to demand his money back. He went up to the Prophet, caught hold of his clothes, and said to him harshly: “Muhammad, why don’t you pay me my due? From what I know of the descendants of Muttalib, they all put off paying their debts.” ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab was with the Prophet at the time. He became very angry, scolded the Jew and was on the point of beating him up. But the Prophet just kept smiling. All he said to the Jew was: “There are still three days left for me to fulfill my promise.” Then he addressed ‘Umar “Zayd and I deserved better treatment from you,” he said. “You should have told me to be better at paying my debts, and him to be better at demanding them. Take him with you, ‘Umar, and pay him his due; in fact, give him 20 sa’ahs (about forty kilos) of dates extra because you have alarmed him with your threats.” The most remarkable thing about this episode is that the Prophet could still behave with such forbearance and humility even after being established as head of the Muslim state of Madinah.

So successful was the Prophet’s life that, during his lifetime, he became the ruler of the whole of Arabia right up to Palestine. Whatever he said, as the messenger of God, was accepted as law. He was revered by his people as no other man has ever been revered. When ‘Urwah ibn Mas’ud was sent to him as an envoy of the Quraysh (A.H. 6), he was amazed to see that the Muslims would not let any water used by the Prophet for ablution fall on the ground, but would catch it in their hands, and rub it on their bodies. Such was their veneration for him. Anas ibn Malik, the Prophet’s close companion says that in spite of the great love they had for the Prophet, out of respect they could not look him full in the face. According to Mughirah, if any of the Prophet’s companions had to call on him, they would first tap on the door with their fingernails. One night, when the moon was full, the Prophet lay asleep, covered in a red sheet. Jabir ibn Samrah says that sometimes he would look at the moon and sometimes at the Prophet. Eventually he came to the conclusion that the Prophet was the more beautiful of the two.

So successful was the Prophet’s life that, during his lifetime, he became the ruler of the whole of Arabia right up to Palestine. Whatever he said, as the messenger of God, was accepted as law. He was revered by his people as no other man has ever been revered.

Arrows rained down on the Prophet from the enemy ranks, but his followers formed a ring around him, letting the arrows strike their own bodies. It was as though they were made of wood, not flesh and blood; indeed the arrows hung from the bodies of some of them like the thorns of a cactus tree.

Devotion and veneration of this nature can produce vanity in a man and engender a feeling of superiority, but this was not the case with the Prophet. He lived among others as an equal. No bitter criticism or provocation would make him lose his composure. Once a desert-dweller came up to him and pulled so hard at the sheet he was wearing that it left a mark on his neck. “Muhammad!” he said. “Give me two camel-loads of goods, for the money in your possession is not yours, nor was it your father’s.” “Everything belongs to God,” the Prophet said, “and I am His servant.” He then asked the desert-dweller, “hasn’t it made you afraid, the way you treated me?” He said not. The Prophet asked him why. “Because I know that you do not requite evil with evil,” the man answered. The Prophet smiled on hearing this, and had one camel-load of barley and another of dates given to him.

The Prophet lived in such awe of God that he was always a picture of humility and meekness. He spoke little and even the way he walked suggested reverence for God. Criticism never angered him. When he used to put on his clothes, he would say: “I am God’s servant, and I dress as befits a servant of God.” He would sit in a reverential posture to partake of food, and would say that this is how a servant of God should eat.

The Prophet lived in such awe of God that he was always a picture of humility and meekness. He spoke little and even the way he walked suggested reverence for God. Criticism never angered him.

He was very sensitive on this issue. Once a companion started to say, “If it be the will of God, and the will of the Prophet ... “ The Prophet’s face changed colour in anger when he heard this. “Are you trying to equate me with God?” he asked the man severely. Rather say: “If God, alone, wills.” On another occasion a companion of the Prophet said: “He that obeys God and His Prophet is rightly guided, and he who disobeys them has gone astray.” “You are the worst of speakers,” the Prophet observed, disliking a reference, which placed him in the same pronoun as the Almighty.

Three sons were born to the Prophet, all of whom died in infancy. His four daughters, all by his first wife, Khadijah, grew to adulthood. Fatimah was the Prophet’s youngest daughter, and he was extremely attached to her. When he returned from any journey the first thing he would do, after praying two rak’at8 in the mosque, was to visit Fatimah and kiss her hand and forehead. Jumai’ ibn ‘Umayr once asked ‘A’ishah whom the Prophet loved most. “Fatimah,” she replied.

But the Prophet’s whole life was moulded by thoughts of the hereafter. He loved his children, but not in any worldly way. ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, Fatimah’s husband, once told Ibn ‘Abdul Wahid a story about the Prophet’s most beloved daughter. Fatimah’s hands, he said, were blistered from constant grinding; her neck had become sore from carrying water; her clothes would become dirty from sweeping the floor. When the Prophet had received an influx of servants from some place, ‘Ali suggested to his wife that she approach her father and ask for a servant. She went, but could not speak to the Prophet because of the crowd. Next day, he came to their house, and asked Fatimah what she had wanted to see him about. ‘Ali told the Prophet the whole story, and said that he had sent her. “Fear God, Fatimah,” the Prophet said, “Fulfill your obligations to the Lord, and continue with your housework. And when you go to bed at night, praise God thirty-three times, and glorify Him the same number of times; exalt His name thirty-four times, and that will make a full hundred. This would be much better than having a servant.” “If that is the will of God and His Prophet,” Fatimah replied “then so be it.” This was the Prophet’s only reply. He did not give her a servant.

The truth revealed to the Prophet was that this world did not spring up by itself, but was created by one God, who continues to watch over it. All men are His servants, and responsible to Him for their actions. Death is not the end of man’s life; rather it is the beginning of another, permanent world, where the good will enjoy the bliss of paradise and the wicked will be cast into a raging hell. With the revelation of this truth also came the commandment to propagate it far and near. Accordingly, ascending the height of the rock of Safa, the Prophet called the people together. First he made mention of the greatness of God. Then he went on to say:

By God, as you sleep so will you die, and as you awaken so will you be raised after death: you will be taken to account for your deeds. The good will be rewarded with good and the evil with evil. And, for all eternity, the good will remain in heaven and the evil will remain in hell.

One who goes against the times in his personal life is faced with difficulties at almost every step, but these difficulties are not of an injurious nature. They may wound one’s feelings, but not one’s body. At the most, they are a test requiring quiet forbearance. But the position is quite different when one makes it one’s mission to publicly oppose convention—when one starts telling people what they are required to do and what not to do. The Prophet was not just a believer; he was also entrusted with conveying the word of God to others. It was this latter role that brought him into headlong collision with his countrymen. All forms of adversity—from the pain of hunger to the trepidation of battle—were inflicted on him. Yet throughout the twenty-three years of his mission, he always remained just and circumspect in his actions. It was not that he had no human feelings in him and, therefore, incapable of bitterness; it was simply that his conduct was governed by the fear of God.

Three years after the Prophet’s migration to Madinah, Makkan opponents mounted an assault on Madinah and the Battle of Uhud took place. At the beginning, the Muslims held sway; but later on a mistake made by some of the Prophet’s companions gave the enemy the chance to attack from the rear and sway the tide of battle in their favour. It was a desperate situation and many of the companions started fleeing from the field. The Prophet was left alone, encircled by the armed forces of the enemy. Like hungry wolves, they advanced upon him. The Prophet started calling to his companions. “Come back to me, O servants of God,” he cried. “Isn’t there anyone who will sacrifice his life for my sake, who will fend these oppressors off from me and be my companion in paradise?’

Imagine how dreadful the situation must have been, with the Prophet crying for help in this manner. Some of his companions responded to his call, but such confusion reigned at the time that even these gallant soldiers were not able to protect him fully. ‘Utbah ibn Abi Waqqas hurled a stone at the Prophet’s face, knocking out some of his lower teeth. A famed warrior of the Quraysh, ‘Abdullah ibn Qumayyah, attacked him with a battle-axe, causing two links of his helmet to penetrate his face. They were so deeply embedded that Abu ‘Ubaydah broke two teeth in his attempt to extract them. Then it was the turn of ‘Abdullah ibn Shahab Zuhri, who threw a stone at the Prophet and injured his face. Bleeding profusely, he fell into a pit. When for a long period the Prophet was not seen on the field of battle, the word went around that he had been martyred. Then one of the Prophet’s companions spotted him lying in the pit. Seeing him to be alive, he cried jubilantly, “The Prophet is here!” The Prophet motioned to him to be silent, so that the enemy should not know where he was lying.

In this dire situation, the Prophet uttered some curses against certain leaders of the Quraysh, especially Safwan, Suhayl and Harith. How can a people who wound their prophet ever prosper!’ he exclaimed. Even this was not to God’s liking, and Gabriel came with this revelation:

It is no concern of yours whether He will forgive or punish them. They are wrongdoers.9 This admonition was enough for the Prophet and his anger subsided. Crippled with wounds, he started praying for the very people who had wounded him. Abdullah ibn Mas’ud later recalled how the Prophet was wiping the blood from his forehead, and at the same time praying:

Lord, forgive my people, for they know not what they do.10

Biographies of the Prophet are full of incidents of this nature, which show his life to be a perfect model for mankind. They show that we are God’s servants, and servants we should remain in every condition. Being God’s humble servants, we should always remain in a state of trepidation before our Lord and the life hereafter. Everything in the universe should serve to remind us of God. In every event we should see the hand of the Almighty, and, for us, every object should portray God’s signs. In all matters of a worldly nature, we should remember that everything will finally be referred to God. Fear of hell should make us live humbly among our fellows, and longing for paradise should impress on us the significance of this world. So conscious should we be of God’s greatness that any idea of demonstrating our own greatness should appear ridiculous. No criticism should provoke us and no praise should make us vain. This is the ideal human character, which God displayed to us in the conduct of His Prophet.

NOTES

1. Konstan Virgil George (b 1917), The Prophet of Islam.

2. Quran, 93:7.

3· Quran, 94:1-3.

4. Hadith of Razin.

5· Hadith of Ibn Hibban.

6. Miswak, a stick used as a dentifrice.

7· Hadith of al-Bukhari.

8. Rak’at, section of prayer.

9· Quran, 3:128.

10. Hadith of Muslim.