Maulana Wahiduddin Khan | The Prophet of Peace, pp. 175-190

The present history of Palestine begins in 1948 in the days of the British Empire when Palestine was divided under the terms of the Balfour Declaration. According to this division, less than half of the land of Palestine was given for settlement to the Jews of the Diaspora and more than half was given to the Arabs who inhabited that land.

The Jews were given this right between the First and Second World Wars under the limited quota system. The expansion of Israel which took place later on was not the result of the Balfour Declaration but was the outcome of the wrong policy followed by the Arabs.

For instance, the unilateral termination of the lease of the Suez Company in 1956, which in any case was going to expire in 1968 according to the pact, naturally had grave consequences. The selling of land to the Jews by the Palestinian Arabs at high prices had similar results.

Who are the Jews or Israelis? They are the descendants of the Israelites, the progeny of Prophet Jacob, and the grandsons of Prophet Abraham. To be more specific, the Jews of today are the descendants of Juda, the fourth son of Prophet Jacob (also known as Israel, which in Hebrew means ‘God’s servant’).

The history of Abraham goes back four thousand years. Abraham had two sons, Ishmael and Isaac. Ishmael, the elder, was the son of Hagar, and Isaac, the younger, was the son of Sara. By the command of God, Abraham settled Ishmael in Arabia and Isaac in Palestine. Isaac had a son called Jacob. He was also called Israel, the progenitor of the Children of Israel. Thus Palestine came to be the homeland of the Israelites, just as Arabia came to be the homeland of the Ishmaelites.

As the Jewish religion is based on race, there is no concept of conversion to Judaism. Due to the purity of this race, in direct line from its ancestors, Isaac and Jacob, the common land of all Jews, regardless of which part of the world they inhabit, is Palestine. The homeland of the Ishmaelites was always and still is Arabia. Both were settled in these lands by the command of God.

After 1948, when a number of these Jews who were living in different countries came to Palestine, the Arabs demonstrated a strong negative reaction to them. The greatest organization of Arabs, Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun, was, in fact, formed as a consequence of these hostile feelings for the Jews. At that time, the slogan of the Arab leaders was ‘We will drive the Jews into the sea.’

The ancient times were marked by intolerance in religious matters, which meant that the Jews had to face unpleasant experiences repeatedly. Over the centuries, wave after wave of them left Palestine, their homeland, in large numbers to go into exile. It is this spread of Jews living outside Palestine which is called the Diaspora. It was under the Balfour Declaration that it was decided that the Jews who were living in the Diaspora would return to Palestine.

After 1948, when a number of these Jews who were living in different countries came to Palestine, the Arabs demonstrated a strong negative reaction to them. The greatest organization of Arabs, Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun, was, in fact, formed as a consequence of these hostile feelings for the Jews. At that time, the slogan of the Arab leaders was ‘We will drive the Jews into the sea.’

The settlement was strenuously opposed by Arab and non-Arab Muslim leaders alike, to the point where the entire Muslim world had turned against the Jews. All kinds of violence, including suicide bombing, were held to be lawful against them. But all these activities targeting the Jews proved to be counterproductive. The direct loss resulting from these activities was as acutely felt by the Muslims as by the Jews in Palestine, and Muslims all over the world shared indirectly in this loss.

This anti-Jewish policy followed by the Arab and non-Arab Muslims clearly went against Islamic teachings. Under the Balfour Declaration, the division of Palestine was intended to facilitate the return of the Jews in the Diaspora to their own homeland, and this is clearly in accordance with the teachings of the Quran. According to the Quran, the Jews in the time of Prophet Moses were directed by God:

‘O my people! Enter the holy land which God has assigned to you.’ (5:21)

Who were the Jews of those times? They were those who were living in the Sinai desert in the Diaspora. The ‘Holy Land’ in this verse refers to Palestine. This verse was addressed to Prophet Moses’ contemporaries, the Jews who were living outside Palestine. The words of the Quran ‘which God has assigned to you’ mean that this return to Palestine was to be exactly in accordance with the law of nature. For, according to this law, any individual or group living in exile has the right to return to his or their original homeland.

Abraham had settled one branch of his family in Palestine. Joseph, Jacob’s son, was also born into this family. Destined by circumstances to reach Egypt, he was ultimately given a high post in the government of the country by the reigning king (one of the Hiksos dynasty), who was impressed by his capabilities.

After his position was consolidated in Egypt, Joseph invited his family, including his father Jacob, to leave Palestine for Egypt. Once settled in Egypt, his people multiplied and gradually became a powerful racial group in the country of their adoption.

During the time of Moses, that is, in the time of the ancient Jewish Diaspora, the plan for these exiled Jews to return to their former homeland was made at the behest of God. In modern times, the plan for the return of the exiled Jews of the Diaspora was executed in terms of the Balfour Declaration.

In the years following Joseph's ascendancy, a political revolution in Egypt put in place a new dynasty that supplanted the Hiksos kings. They adopted the title ‘Pharaoh.’ It was under these new rulers that the Israelites were subjected to oppression, until the advent of Moses, who succeeded in leading the Israelites out of Egypt into the Sinai desert. This was the first stage of their journey. The second stage of their journey was to enter Palestine and settle there in their former homeland.

During the time of Moses, that is, in the time of the ancient Jewish Diaspora, the plan for these exiled Jews to return to their former homeland was made at the behest of God. In modern times, the plan for the return of the exiled Jews of the Diaspora was executed in terms of the Balfour Declaration.

The Problem of the Return to the First Qibla

Muslims in general regard the present problem of Palestine as that concerning the return to the first qibla. They point out that when Prophet Muhammad built a mosque in Madinah and laid down that five prayers had to be ritually recited in it, he followed the Jewish tradition in making al-Masjid al-Aqsa his qibla for a period of sixteen months.

However, this is a misunderstanding. When Muslims migrated to Madinah, they actually worshipped at the direction of the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), the Jewish qibla, and not at the direction of Al-Masjid al-Aqsa.

At the end of this sixteen-month period, the command was revealed in the Quran to change the qibla. So the Prophet adopted the Kabah as the permanent qibla in accordance with God's command. Referring to this incident, Muslims claim that the problem of Palestine is one of the return to the first qibla. Thus they make the point that this problem is not a national but religious issue for the Muslims. This concept is based entirely on a misunderstanding. The first qibla has nothing to do with al-Masjid al-Aqsa. The name al-Masjid al-Aqsa in the following verse of the Quran has not been cited in the sense of a particular mosque.

‘Holy is He who took His servant by night from the sacred place of worship [at Makkah] to the remote house of worship [at Jerusalem]—the precincts of which We have blessed.’ (17: 1 )

The above verse just means a place of worship situated at a distance. It is called the farthest place of worship because it is situated at a distance of 765 miles from Makkah. Al-Masjid al-Aqsa, in this context, refers to the Jewish place of worship, that is, the Haykal Synagogue.

This Jewish synagogue, built by Solomon in 957 BC, was razed to the ground in 586 BC by the king of Babylonia, Nebuchadnezzar II. After a long period of time, the Jews rebuilt their place of worship. This was again reduced to ruins in AD 70 by the Romans. At present only one wall of the building is left. This is called the ‘wailing wall’ or the ‘western wall.’ At the time of the revelation of the Quran, there was no building there; it was only a vacant site. In AD 638, in the time of the second caliph, Umar Farooq, the Muslims entered Jerusalem. Caliph Umar did not have any structure erected on this site. During the Umayyad rule, Caliph Abdul Malik bin Marwan (d. 705) had the present al-Masjid al-Aqsa built in AD 688.

There is another building on the campus of al-Masjid al-Aqsa, which is called the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra). The sacred rock of the Jews has been situated there since ancient times. It was on this sacred rock that Caliph Abdul Malik ibn Marwan built the present dome in AD 688. It was this sacred rock or Dome of the Rock, the qibla of the Jews, which was made the Muslim qibla temporarily by Prophet Muhammad after his emigration to Madinah. It is this Dome of the Rock that is known as al-Quds and, by extension, this entire area of Jerusalem is called al-Quds.

Muslims in general regard al-Masjid al-Aqsa as the first qibla, and it has become a symbol of the Palestinian struggle. But the mosque has nothing to do with the first qibla. If there is any first qibla, it is the Dome of the Rock rather than al-Masjid al-Aqsa. Furthermore, when Prophet Muhammad was in Makkah, he used to say his prayers after turning in the direction of the Kabah. After his emigration, for about sixteen months, he said his prayers in the direction of the Dome of the Rock. Afterward, in obedience to God's command, he again started saying his prayers in the direction of the Kabah. In this respect, the Dome of the Rock is the middle qibla and not the first.

When the exiled Jews started coming to Palestine to be settled there, in the wake of the Balfour Declaration of 1948, the only reaction from the Arabs was violent jihad. The Arab countries started funding the Palestinian Arabs on a large scale. They wanted to crush the Jewish state, but they totally failed to achieve their objective.

In light of this fact, the expression ‘return to the first qibla’ is totally without meaning. If this supposed return is attributed to al-Masjid al-Aqsa, it should be noted that it never was the qibla of Prophet Muhammad. At the time of the Hijrah (AD 622), there was only a vacant site there on which a Jewish synagogue had previously stood. There was no mosque in existence at the time of the Prophet. As far as the Dome of the Rock is concerned, there is no question of its return. It was the Jewish qibla earlier and it is the Jewish qibla today. The demand for the return of the Dome of the Rock is as invalid as the demand (if there is any such demand) of the polytheists to return the Kabah to them, as at one time it housed their deities.

When the exiled Jews started coming to Palestine to be settled there, in the wake of the Balfour Declaration of 1948, the only reaction from the Arabs was violent jihad. The Arab countries started funding the Palestinian Arabs on a large scale. They wanted to crush the Jewish state, but they totally failed to achieve their objective.

This was undoubtedly a great mistake on the part of the Arab leaders. Had these Arab leaders learned any lesson from Islamic history, they would have certainly found that there was a better option before them. That was to welcome those Jews as their neighbours and work for the progress and development of Palestine in collaboration with them. These Jews, coming mainly from Western countries, were highly educated, had great expertise in modern science and technology, and as such had the ability to become the best partners the Arabs could hope for as far as the progress and development of Palestine was concerned. But in their welter of emotion, the Arab leaders failed to understand this positive aspect of the matter.

There were very fine examples in the history of Islam of this collaboration between the Jews and the Muslims. When Muslim empires were being established, Muslims undertook the task of translating into Arabic ancient books available in Greek and other languages, which they found in different countries. Translation bureaus were set up and a great number of ancient books were translated under the auspices of institutes such as Bait al-Hikmah, which was established in Baghdad in AD 832, and Dar al-Hikmah, which was set up in Cairo in AD 1005, both under direct state patronage. Later, when the Arabs entered Spain and brought it under their control, they established great academic and educational institutions in Cordoba and Granada where these Arabic translations were rendered into Latin. These Latin translations were again rendered into different European languages. Not only were translations undertaken but also, side by side, different kinds of research and investigations were carried out on a large scale.

These academic activities led directly to the Renaissance in Europe. In this way, the Muslims of those times acted as a bridge between the ancient traditional age and the modern scientific age.

In the wake of the Balfour Declaration, a similar opportunity presented itself to the Palestinians, but, blinded by their emotions, their Arab leaders misled them and launched them on the path of confrontation rather than that of collaboration. The Muslim failure to avail of this opportunity put an end to the realization of a great history in the making.

This fact has been generally acknowledged by Western historians. For instance, acknowledging the contribution of the role of the Arabs, Robert Briffault writes, ‘It is highly probable that but for the Arabs, modern industrial civilization would never have arisen at all.’ (Robert Briffault, The Making of Humanity, p. 190)

How did the Arabs perform this great role in the field of learning, especially when no such academic tradition existed among them? The answer is that this feat was achieved by them through their collaboration with others, such as the Christian and Jewish scholars who worked in the institutions established by the Arabs in Iraq, Egypt, and Spain. The result of this joint contribution is that grand academic history of medieval times on the basis of which Western Europe made tremendous progress. (Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs, Macmillan Press, 1979)

In the wake of the Balfour Declaration, a similar opportunity presented itself to the Palestinians, but, blinded by their emotions, their Arab leaders misled them and launched them on the path of confrontation rather than that of collaboration. The Muslim failure to avail of this opportunity put an end to the realization of a great history in the making.

A comparison between the two parts of Palestine—one under Arab rule and the other under Jewish rule—is a telling example of what would have been had the two communities entered into a collaborative exercise. The Jewish-ruled Palestine which, before 1948, was a barren desert has been converted into green fields and orchards. By contrast, the Arab-ruled Palestine is still in the same backward condition as it was prior to 1948. The Palestinians are still waging a futile battle under their unwise leaders. Earlier their goal was to bring Palestine back to its original state, as it was in the pre-1948 period. Now their goal is to bring Palestine to the state of 1967. Meeting both these targets is impossible. This is akin to reversing the course of history and history itself is a witness to the impossibility of such a reversal. The first option for the Palestinians was to willingly accept the status quo of 1948. Now their second option is to accept the present status quo. If they lose this second opportunity as well, they are not going to find a chance to exercise a third option. The third option for them will be death and destruction rather than life and construction.

‘Status-quoism’ means acceptance of the current situation as it is. This is not a matter of weakness. It is a wise policy of a high order, in accordance with the law of nature. In this world there always exists some controversial issue or the other. Along with this, the very system of nature demands that in every situation there should be opportunities to solve problems. But given the present state of affairs, a result-oriented policy would be to ignore the problems and seize whatever opportunities there may be left for the betterment of the situation. Becoming entangled with controversial issues always comes at the cost of losing such precious opportunities and leaving the situation unimproved.

In Palestine, the Arab leaders have been fighting for their lost land for a long period of time. But if we look at it from the perspective of results, we find that all their efforts and sacrifices have been wasted. Not only have they failed to achieve the target of recovering their land, but they have missed out on precious opportunities to make other kinds of progress, thereby incurring a great loss.

The present state of affairs in Palestine is a crisis situation, which benefits neither the Arabs nor the Israelis. It is in the interests of both to think seriously and without prejudice, in order to take some decision to normalize the situation. However, both parties will have to adopt a realistic approach to the matter.

The present age is one of globalization. In the agricultural age of ancient times, land was of the utmost importance; but modern communications have now reduced land to a secondary position. Of prime importance now are the opportunities presenting themselves, thanks to globalization, in equal measure to all. Now anyone working in a modest office can avail of opportunities available the world over. Given this situation, fighting for the acquisition of a piece of land is anachronistic in nature and can never yield positive results.

The present state of affairs in Palestine is a crisis situation, which benefits neither the Arabs nor the Israelis. It is in the interests of both to think seriously and without prejudice, in order to take some decision to normalize the situation. However, both parties will have to adopt a realistic approach to the matter. Any condition that is not acceptable to both sides will be unrealistic and will lead to a state of impasse.

As I understand it, the only practicable solution to this problem is for the Arabs to abandon all kinds of terrorism. This is the first prerequisite. Trying to find a solution without fulfilling this condition is to travel in an imaginary world—on a journey that will never reach its destination. So far as Israel is concerned, it will have to give the Palestinian Arabs (residing in Palestine) the same rights as are enjoyed by other residents under the constitution. If both these points are accepted in principle, a practical settlement can be arrived at through peaceful negotiation.

There is much talk about giving land for peace. But on the basis of my knowledge and information, I consider this suggestion totally impracticable. The only workable formula in this context is ‘rights for peace.’ Its greatest benefit would be that by accepting it the Arabs would immediately be able to find a starting point for a better future. At the moment, the Palestinian movement is caught in a blind alley, but by accepting the notion of ensuring peace on their being given their rights, the deadlock would instantly be broken and the Arabs would see before them a golden opportunity to begin their journey on the highway of progress.

On the issue of Palestine, all the Muslim leaders, Arabs, and non-Arabs alike, have only one thing to say, and that is that Israel should return the land occupied during the war, and only then will the Palestinians stop all violent activities. Acceptance of this proposal is supposed to lead to 'peace with justice'.

As we know, despite a huge amount of effort, it has never been possible to put this proposal into effect. The sole reason for the failure of this formula is that it is unrealistic. No unrealistic formula can ever meet with success in this world of realities. This world being based on the eternal laws of nature, only that formula can meet with success which is reinforced by these laws.

The truth is that according to the laws of nature, justice is not a part of peace; therefore, bracketing justice with peace may have meaning in terms of human aspirations, but it is a fallacy from the point of view of reality. Once peace is established, justice is not an automatic sequel. It only opens opportunities. The task of achieving justice begins when we grasp these opportunities to establish it. The truth is that whenever one receives justice, it is the result of one's own hard work—whether acting as individuals or as groups. Prophet Muhammad provides a very clear historical example of this in his method of negotiating the Hudaybiyya peace treaty (as we saw in chapter 20).

In terms of my own experience, I can clearly say that the Palestinians are a vibrant people, possessed of great potential, both physical and intellectual. This is but natural, for they have been brought up in a geographical region that the Quran (17:1) describes as having been 'blessed' by the Almighty.

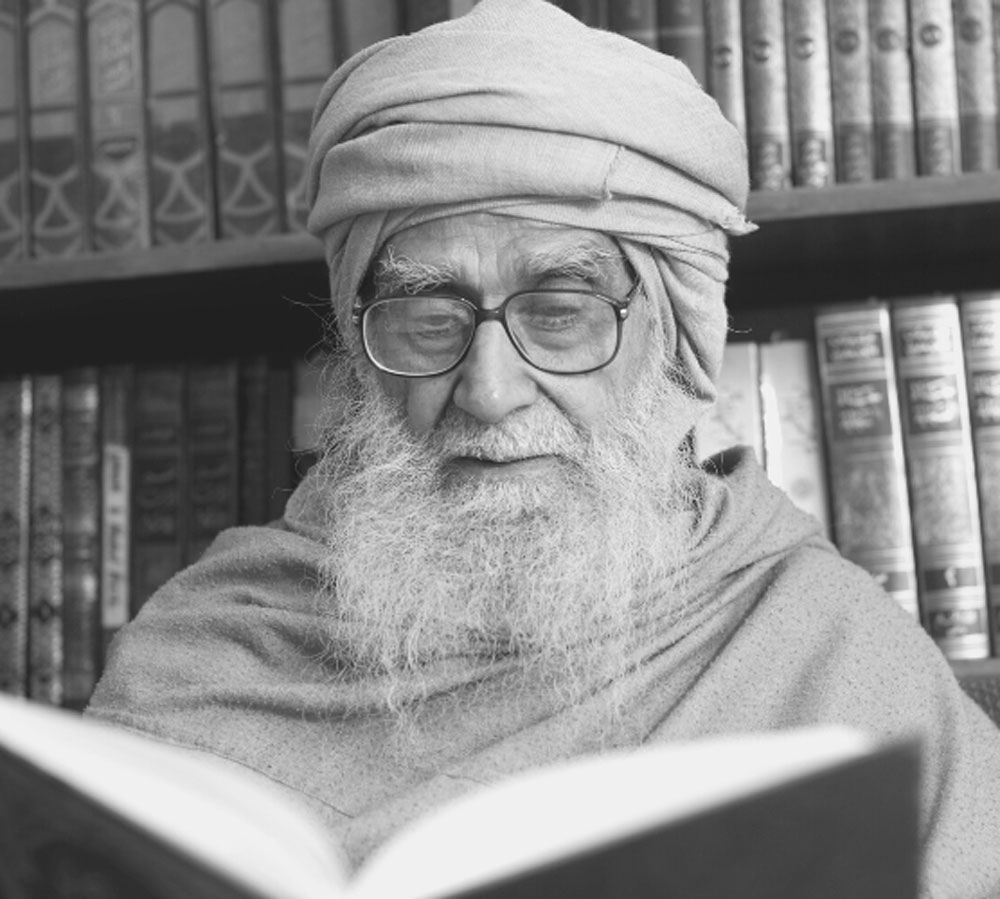

By the grace of God, I have traveled to Palestine three times, in August 1995, in October 1997, and then again in October 2008. These visits gave me the opportunity to observe Palestine firsthand. Moreover, I have met a number of Palestinian Muslims in and outside Delhi, and have also familiarized myself with their situation by reading a number of authoritative books on Palestine.

In terms of my own experience, I can clearly say that the Palestinians are a vibrant people, possessed of great potential, both physical and intellectual. This is but natural, for they have been brought up in a geographical region that the Quran (17:1) describes as having been 'blessed' by the Almighty.

The Palestinians, endowed with exceptional natural qualities, are capable of undertaking great tasks, but it is very tragic that it has not been possible for them to realize their own potential. The principal reason for this tragedy is that their leaders have launched them on the path of violence and hatred. They have wrongly come to regard the land they are struggling for as of the greatest importance and are sacrificing their lives to acquire it. They are unaware of the fact that the life of a Palestinian is a thousand times more precious than the land which they have been making futile efforts to acquire for so long. Had Palestinians been aware of the possibilities of the modern age, they would certainly have availed of the opportunities it offered, not only at the level of Palestine but also at an international level. They would thus have made great progress.

Peaceful action, in accordance with the laws of nature, increases human creativity and is therefore at all times and in every way superior to violent action. Those who employ peaceful means for achieving their goals steadily evolve into creative groups. On the contrary, those who opt for the way of hatred and violence perpetually suffer from an erosion of their creativity, and it is almost impossible to compensate for the various kinds of losses resulting from their violence. While success crowns the actions of the creative groups in this world, uncreative groups are destined for every kind of failure. This is an eternal law of nature. There is no exception to it.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to say that Islam is a peaceful religion, in the full sense of the term. We would not be wrong in saying that Islam is the first religious system in human history that offers a complete ideology of peace. By adopting it, Prophet Muhammad successfully brought about a peaceful revolution in the real sense. The ideology of Islam banishes the notion that there can be anything acceptable about terrorism. Islam is a completely peaceful religion and the Islamic method is a peaceful method. By following the ideology of peace, each individual's mind can be re-engineered away from the culture of violence and closer to the culture of peace.

The essence of Islamic teaching on the subject of peace is underscored by an incident that took place when Prophet Muhammad returned from the Tabuk campaign in 9 AH. When, along with his 30,000 companions, he reached Madinah, he said to one of them, ‘We have come back from a smaller jihad to a greater jihad.’ (KashfulKhifa, Vol. 2, p. 345)

What did the Prophet mean by ‘a smaller jihad’ and ‘a greater jihad’?

‘A smaller jihad’ connotes a temporary jihad and ‘a greater jihad’ connotes a permanent jihad. A permanent jihad is one which is a part of the daily life of a believer. In this present world, where man is undergoing a divine test, a believer has to lead a principled life, eschewing all kinds of temptations and provocations, and adhering with unflagging zeal to Islamic principles. That is why it is called a greater jihad. So far as the smaller jihad is concerned, it is, in fact, another name for defensive war. It takes place infrequently and only as the occasion warrants it. It is not a permanent feature of Islamic life.

Prophet Muhammad was born in AD 570. He received his prophethood on 12 February 610 in Makkah. He died on 8 June 632 in Madinah. Thus his prophetic period, according to the Christian calendar, lasted twenty-two years and three months. In this entire period, only four short battles took place: the Battle of Badr (2 AH); the Battle of Uhud (3 AH); the Battle of Khaybar (7 AH); and the Battle of Hunayn (8 AH). On all these four occasions, the battles, or rather skirmishes, lasted for only half a day. That is two days in total. If you count the days of his prophetic period, the total comes to about 8130 days. So during this long period, the Prophet and his Companions were engaged in a peaceful struggle for 8128 days and they fought defensive battles for only two days. It would thus be appropriate to say that, in Islam, peace is the rule and war the rare exception.