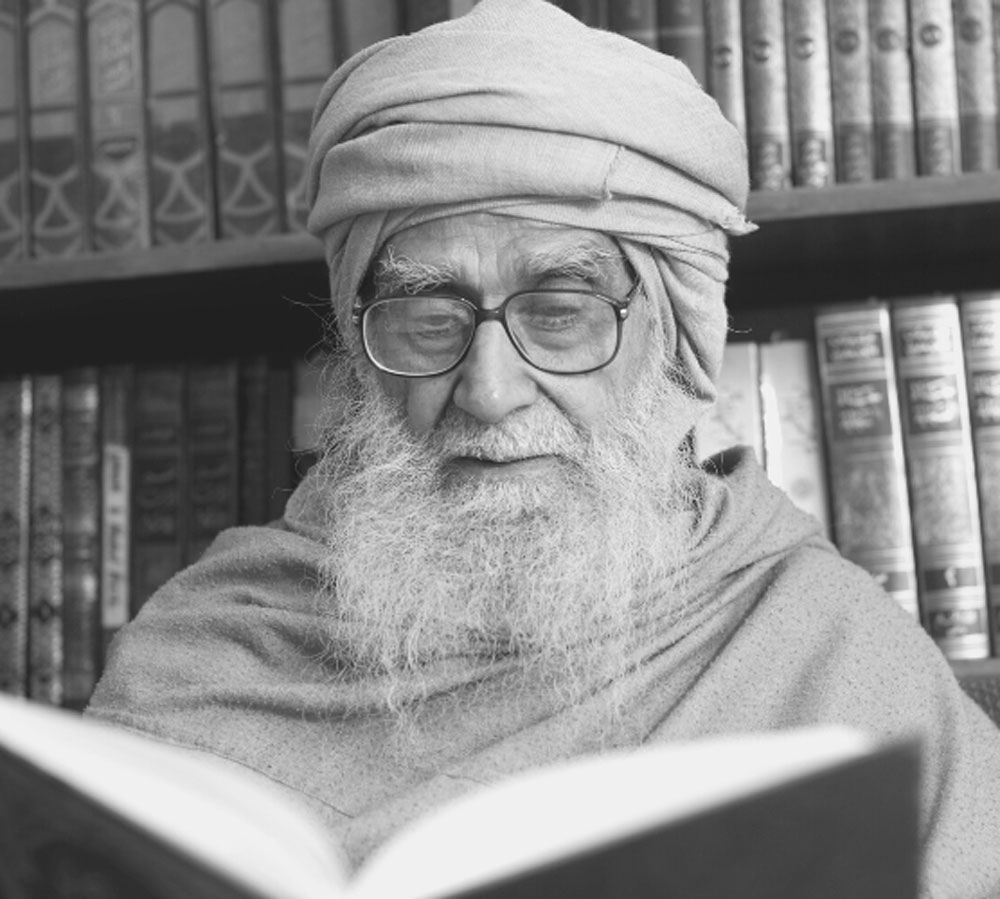

Maulana Wahiduddin Khan I Hindustan Times I April 25, 1995

When an enraged mob of Hindu fanatics demolished the Babri Masjid of Ayodhya and replaced it with a makeshift mandir, it became an act, which was both climactic and terminal. It was not the peaking of an upsurge, but its end. Every destructive activity has an outer limit, and when this limit is reached, no further destruction can take place.

Those gifted with far-sightedness realised on December 6 itself that the destructive moment, in accordance with the laws of nature, would lose momentum and come to naught. However, there were many who failed to come to a timely appreciation of history's verdict. They continued to fear another "December 6." Now, when the actual state of affairs has become an open book, there is no room for anyone to doubt that as from now, this dark chapter is finally closed, making way for brighter and more hopeful prospects in the history of India.

When it comes to the crunch, no such movement can proceed successfully without an enthusiastic response from the public. Once the public becomes apathetic, such a movement loses ground and simply peters out. Events have shown that this is a dead issue. Neither Hindus nor Muslims have any zeal left for further action; it is no longer possible for leaders to whip up either community to a frenzy on this score. This being so, why should there be any residual element, which still expects this movement to continue?

After the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board held a meeting in November 1993 in Bombay, at which a resolution was passed that all the Muslims India must assemble in the mosques on December 6, 1993, to pray for the recovery of Babri Masjid. However, opinions differed on the date to be fixed, as a majority of the member felt that Muslims would not, in fact, gather at the mosques on December 6. A via media was found by changing the date to December 3, three days in advance of the demolition date, because, December 3 being a Friday, the Muslims would of their own accord be gathering in the mosques to offer namaz. In this way, there would at least be the outward appearance of the Muslims having observed that day, as a day of prayer for the Babri Mosque at the behest of their leaders.

December 6, 1994, was the second anniversary of Babri Masjid demolition. However, this time the Muslims Personal Law Board did not attempt to make any such announcement, even to make a show of their having been a demonstration. They had learnt with their very first experiment that Muslims had very soon dismissed the Babri Masjid issue from their minds. It was just not possible to mobilize them.

However, certain other leaders, who were not shrewd enough to acknowledge this, proceeded to announce the second anniversary of the Babri Masjid's demolition in grand style. Having formed the All-India Babri Masjid Rebuilding Committee- an organisation which existed more on paper than in actuality- they announced that along with four thousand Muslims, they would march to Ayodhya on December 6 in order to say their Zuhr prayer in that mosque.

But the so-called Babri Masjid Rebuilding Committee failed miserably to arouse any fervour among Muslims on this issue. What in fact happened was that on December 5 a mere 50 Muslim zealots boarded a bus in Delhi, and when they were prevented by the police from going any further than Ghaziabad, they all quietly came back to Delhi without having clashed with the police. (Qaumi Awaz, December 6, 1994).

Certain Hindu leaders for their part announced that they would launch a campaign to assemble five lakh Hindus, who would celebrate the 'victory day' by entering Ayodhya on that day. But they too failed to rally their own people to the cause. All that happened was that just a few hundred Hindus reached Ayodhya and, after performing their routine pooja, they went back. The extremism of just a few Hindu leaders had no appeal for the masses.

It is an undeniable fact that both the Hindu and Muslim public have already put the issue of Ayodhya behind them. It is high time now that both communities diverted their full attention to more constructive activities.

The editorial of The Hindustan Times of December 8, 1994, entitled 'Hope on Ayodhya' points out that it is to the credit of the nation that the second anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Masjid passed off without any untoward happenings in any part of the country. Time has been a great healer. The bitterness and bad blood generated two years ago in the wake of the Ayodhya tragedy seem to be disappearing. It is evident that the public are no longer willing to follow their leaders on this issue. They are not going to allow themselves to be led into excess in the name of religion. There seems also to be a parallel change in the attitude of the Sangh Parivar, if the very conspicuous absence of the V.H.P. supremo, Mr. Ashok Singhal, from Ayodhya on December 6, 1994, is anything to go by.

It would be wholly accurate to say that the reason for the present low-key approach of the leaders to this issue is the poor response from the people to their aggressive stance. Where the participation of the public had bloated the matter out of all proportion, its present non-cooperation will deal it a death blow. It is seldom that the public can be aroused more than once on issues of such intense emotion. With the passage of time, the pressure of the actual problems of life comes into play as a check on any such arousal. No nation can fail to see the error of attempting to make a non-issue into an issue over a long period of time.

It is human nature to look towards the future and consign the past into oblivion- a law of nature to which Indians would do well to bow. It should be appreciated that the present circumstances- with all obstacles cleared from the path- are now fully ripe for non-partisan action of a positive and constructive nature.

The majority of people in India are either illiterate or semi-literate. Approximately half of the country's population is suffering from poverty and unemployment. Corruption of all kinds has led the country to the verge of ruination. Nowhere is justice obtainable in the courts. The goals of sterling character and national unity are yet to be attained. A number of problems of increasing gravity are still facing our country. The plight of our nation simply cries out for new solutions and freshness of approach.

It is therefore, the duty of all concerned persons to identify and grasp whatever opportunities present themselves for the construction of a new India.